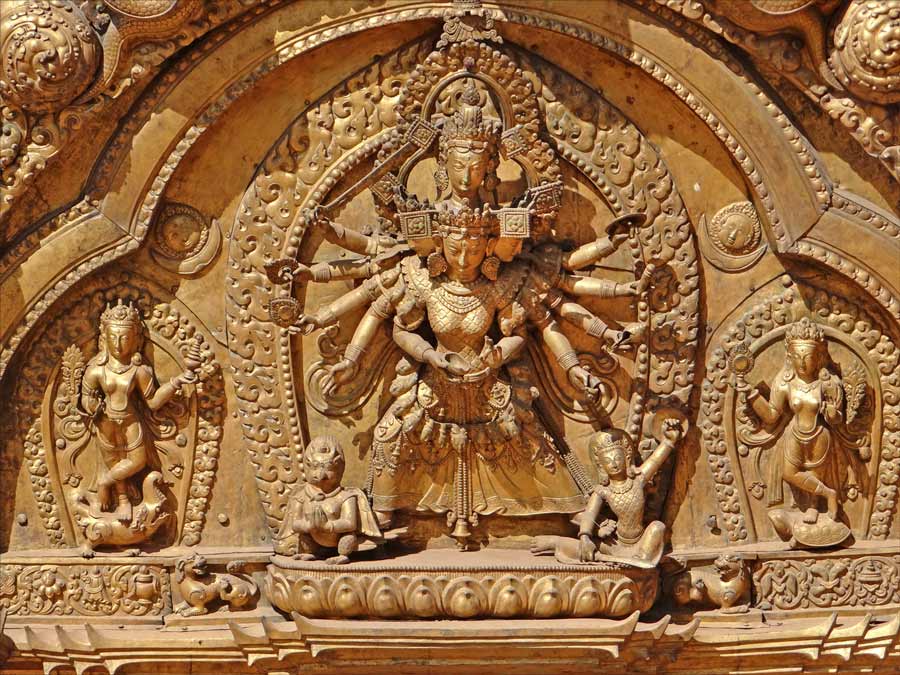

Torana de la porte d'or (Bhaktapur)

Read Previous Parts in this Series

The Matrikas and Mohani

The harvest ritual, Mohani, begins on the New Moon of September or October and ends on the full moon every year. It marks the return of the collective form

of the Goddess as the Nine Durgas (a nine Goddess variation of the Asta Matrika grouping)[xiii], who are propitiated and worshiped as an invocation for

protection from the natural forces that threaten the agricultural cycle as well as from forces that threaten the moral order of the city (Levy 1992, 555).

During the festival the mythic drama of Goddess Durga’s victory over the asuras (demonic forces) is reenacted through many rituals such as recitation of

the entire puranic epic, the Devi Mahatmya, animal sacrifice, and dance.

The rituals are structured around welcoming the return of Devi in collective and singular forms with the rice harvest after her long sojourn in the fields

and other realms (Levy 1992, 503). This festival most likely originated in indigenous traditions honoring the bountiful earth as mother, yet its meaning

and rituals were reformed during the medieval period to include a glorification of the martial arts and the king’s power as well as to invoke protection

for the established order (Harper 2002, 115-128). Harper asserts that a reformation of older religious systems relocated the Matrikas in the Hindu pantheon

(Ibid.) In the merging of the martial and generative qualities of Goddess, we find “the success of the agricultural cycle, the generative powers of earth,

seed, and weather are now allied with the force of the warrior, kshatra, in the battle against the forces of disorder at the boundaries of the

heavenly city of moral gods” (Levy, 1992, 560). In order to reinforce order within Bhaktapur and consecrate the land into a livable sphere during the next

agricultural cycle, a series of processions around the outer eight Matrika shrines, through the twas, and into the center of the city take place

(Levy 1992, 561).

During the first nine days of the festival, each day is devoted to one aspect of Devi in Her Matrika manifestation and that particular shrine is given

special attention. Every morning the participants begin paying homage to Brahmani in the east and continue clockwise to shrines in each of the cardinal

directions and intermediary points[xiv] of the other seven shrines of the Asta Matrikas. As mentioned earlier, there are additionally eight dyoches

(Newari for god house (Levy 1982, 231)) inside the city that spatially relate to each outer shrine. Finally, after visiting the external and internal

shrines, the devotees come to the center pitha at the royal palace, which houses the royal patron deity of Bhaktapur, Taleju, and in the case of

Mohani, the ninth goddess, Tripura Sundari of the Nava Durga, another collective variation of the Asta Matrika.[xv] By circumambulating the borders of the

city and the central shrine, the participants have the opportunity to not only renew protection for the space within and around the boundary places, but

also to engage directly with these otherwise avoided realms of existence. The inhabitants are thus not only outside witnesses to the festival rituals, but

also become Devi in their direct participation (Levy 1992, 556).

Ashta-Matrika

The festival is loaded with agricultural symbolism. Khanna notes, “...the festival performance reveals that the roots of this worship lie in

nature-oriented, village-based agricultural traditions of India, which are intimately bound to seasonal rhythms and crop cycles” (Khanna 2000, 475). I will

mention only a few elements that are important to this study. First, at the most astrologically auspicious time on the first day of the festival, soil from

the riverbank or a tirtha near each of the Matrika shrines is placed in the corner of a room in every home, and barley seeds are planted in and

around a kalasha or water pot, representing the womb of the Goddess. If these seeds are properly worshiped, they begin to sprout on the fifth or

seventh day of the festival. These shoots symbolize the tusks of the Matrika, Varahi, or even symbolic swords Durga uses in the great battle against the

demons that takes place on the eighth and ninth day (Levy 1992, 531). A merging of agricultural and martial interpretations that reflect the reformation of

agrarian rituals into orthodox practices is evident here.

On the seventh day, known as Fulpati, which means “the sacred flowers and leaves” (Anderson 1988, 146), the outer circumambulations to the Matrika shrines

continue to take place, yet the focus shifts to the central Goddess, Taleju. Whether through goat blood offerings to Taleju in preparation for the great

sacrifice that will occur the following night on Kalaratri (Levy 1992, 531- 538) or shifting the ritual focus from the peripheral shrines to Her central

one, the intention behind these practices is to imbue the internal spaces of the city with the Goddess’ protection and sustenance.

Etymologically, the name Taleju, itself, has agricultural and sexual connotations and points to the ancient roots of this festival: “the root word tala...might be related to the same term that meant ‘field’ or ‘hamlet’ in ancient India and Nepal, thus a gramadevata or village tutelary”

(Slusser 1982, 317). It may also “derive from the tantric designation for genitalia” (Ibid.). In the name of this central Goddess, who embodies the full

power of all the Matrikas, we are again reminded of the interconnection between female sexuality and the agricultural cycle.

On the eighth day, Kalaratri or “Black Night” a massive slaughtering of goats and buffaloes continues through deep devotional practices in the internal

sphere of the city—primarily at the Taleju temple and in individual homes. Through these practices Devi is provided with renewed strength to battle the

demonic forces that threaten to destroy the stability of the cosmos. Such sacrificial propitiations bid Her to provide sustenance and protect from

destruction throughout the next yearly cycle. Levy notes,

“This sacrifice not only is a mimesis of the death and regeneration of the agricultural cycle but

also has as one of its implications the forceful binding of individuals-who represent another fertile and dangerous outside-to the city’s social and cultural order”(Levy 1992, 561).

On the ninth day a group of thirteen men representing the Matrikas in their variation as the Nine Durgas and four other minor deities prepare for a dance

that will take place in the twas and outer environs over the next nine months. These rites that take place at the Matrikas’ shrines reveal

vestiges of Kaula and Tantric rites and reinforce the intention of offering the human body as a receptacle for cosmic power. The dancers recite mantras at

their respective Matrika shrines in order to ask for the Goddess’ permission to dance Her energy. Transgressive rites, which I previously discussed, such

as alcohol consumption and animal sacrifice that lead to spirit possession, are part of the preparatory rites at the shrines. In performing such

specialized and antinomian rituals at the shrine of the Goddess, the dancer becomes possessed with Her energy.[xvi] These dances begin with much shaking,

yelling, and frenzied movements, which signifies to the inhabitants of the city that the bodies of these men are housing the elemental forces of the

goddesses. The Matrika dances are twa-based dramas that remind the people of their moral obligations as well as provide a structured environment

for the people to engage with these natural elements in the hope that they will not come unbidden into the internal space throughout the rest of the year

(Levy 1992, 571-576). So begins the goddesses’ nine-month cycle of dancing through Bhaktapur and out into surrounding villages.

On the tenth day when the Goddess is victorious over the threatening forces, there is movement out of peripheral spaces (Levy 1992, 571). The

representative icons of the asuras that have been housed in people’s homes are removed and destroyed and Goddess in her collective form as the Nine Durgas

continues to “dance” through the various twas. The shoots of the jamara (barley) plant are cut and worn behind people’s ears signifying

the blessing of the Goddess. Red tikas made of curd, rice, and red vermillion, are smeared on one’s foreheads, another mark of the Goddess’

blessing and protection.

Only on this day is Taleju taken out in the street for the yearly darshan, when Goddess is taken out to view and be viewed by Her devotees.

Alcohol consumption, which is not normally tolerated within the orthodox tradition, and bawdy public comments are also tolerated as part of the celebration

of Her victory.

Through these various rites, the Mohani festival gives all inhabitants a chance to participate in ways that would be polluting or threatening outside of

this ritual context. As Levy points out, the Matrikas “represent other realms and ideas that must be dealt with in other ways (1992, 284).” In this regard

they are the elemental forces that only operate through spiritual, sexual power, not the usual “moral interactions and manipulations” that make up the

ordered state of city life (Ibid, 284).

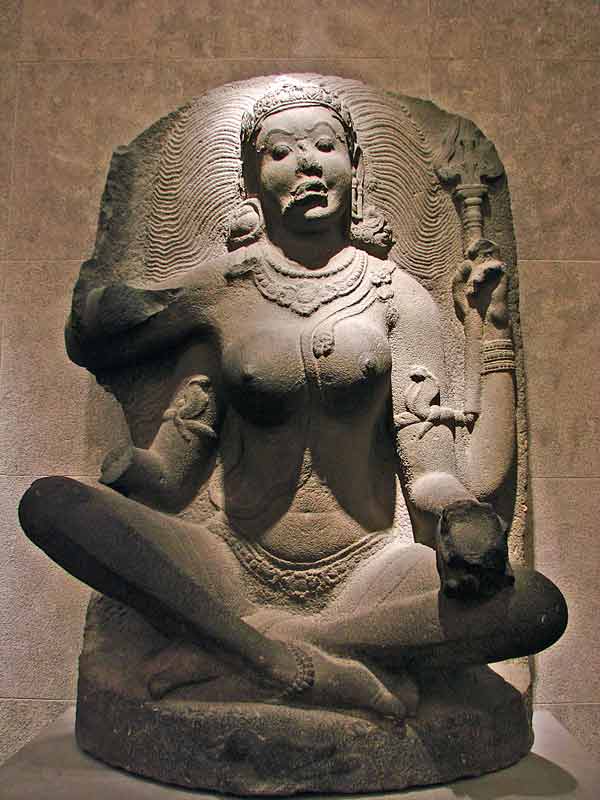

Matrika, India, Museum Guimet

Interpretations of Blood Sacrifice and Its Influence on the Spatial Organization of Bhaktapur

A millennia-old association between vegetative rituals and sacrifice has existed which explains the festival’s bloodshed. David Kinsley provides a

convincing explanation for the use of blood in harvest rituals. He writes:

My suggestion is that underlying blood sacrifices to Durga is the perception, perhaps only unconscious, that this great goddess who nourishes the crops and

is identified with the power underlying all life needs to be reinvigorated from time to time. Despite her great powers she is capable of being exhausted

through continuous birth and the giving of nourishment. To replenish her powers, to reinvigorate her she is given back life in the form of animal

sacrifices. The blood in effect resupplies her so that she may continue to give life in return (Kinsley 1996, 112-113).

During the festival, sacrifice is viewed as crucial in maintaining natural cycles and in invoking the Matrikas’ favor and protection. The life force energy

that is contained in blood is deemed necessary to perpetuate the cycle. Therefore, the Matrikas continue to be propitiated with animal blood today. Perhaps

the contemporary use of animal blood has replaced menstrual blood, “the first ethical blood of the altar” (Durdin-Robertson, 1977, in Noble 1993: 9).

Tantric practitioners and Kaula practitioners have relied on the potency of menstrual blood and other sexual fluids in their secret rites and practices for

centuries.[xvii] “The close association, even interdependence, between human sexuality and the growth of crops is clear in many cultures” (Kinsley 1986, 113).

Perhaps a celebration of the connection between the rice cycle and menstrual cycle is still expressed (albeit unconsciously) in the tikas of rice,

curd, and red powder used on the tenth day to celebrate Her victory.

As we have seen from the female body-centered etymological references to sacred sites within and around Bhaktapur (dhokas, pithas, maithan), I contend

there are strong associations with the ritualistic blood mysteries that take place in these locales and the interrelationship between women’s bodies, the

cosmos, and the earth. During Mohani one of the central representations of worship is the kalasha, symbolic of the womb of Goddess. In fact, one of Her

numerous epithets is Bhagavati.[xviii] Bhaga means womb and power. In addition, the dates of the Mohani festival are calculated by the lunar

calendar, just as women’s menstrual cycles respond to the lunar cycle. In his article, “Women, Earth, and the Goddess: A Shakta-Hindu Interpretation of

Embodied Religion” Patel notes,

For a Shakta-Hindu menstruation is a holistic concept. It is a religion (dharma). The term ritu, which signifies menstruation, also signifies the

cyclical changes of the seasons as well as the orderliness with the cosmos. Thus, it is believed that the menstrual cycle in the female body corresponds to

and represents, the cyclical change of season and the orderliness in the universe”(Patel 1994, 72-73).

While today menstrual blood is deemed polluting within orthodox tradition, I would argue that this is a degenerate and inverted response to its ultimate

potency. Beginning in the 11th century there was a revitalization of the Kaula tradition in Bhaktapur that flourished along with other Tantric practices

under Malla rule. In the Kaula tradition, as we have seen, Goddess is the primordial source of the clan and two of Her epithets take on particular

significance for this discussion: “She is kulagocara, ‘she who is the channel of access to the clan’ and kulagama, ‘she whose issue of blood gives rise to

the clan’”(White 2003, 19). Could the nine-month cyclical dance of the Nine Durgas be rooted in an ancient mimesis of a woman’s pregnancy? Is it mere

coincidence that the many districts that make up the spatial locality of Bhaktapur are referred to as twa, meaning clan and branches of a tree, a

genealogical and essentially feminine symbol? Does this terminology refer to an ancient ideology—centered on matrifocality and the Earth Mother—that has

influenced the layout of the city? As White points out, “the goddess through the channel of her vulva and its mission is the mother of the entire flow

chart of the clan indeed of the entire embodied cosmos” (Ibid., my italics).

Concluding Remarks

Considering the ritual and spatial significance of ancient sites to goddesses who govern the realms of sex, birth, and death, illness and health, order and

chaos within and around Bhaktapur, it seems the city’s geographical organization is rooted in primordial ideologies that conceive of women and earth as

sacred. My contention is practices that are now peripheralized actually stem from early traditions where the connection between female sexuality and the

cyclical fertility of Mother Earth was consciously integrated into ritual practices. As is evident in traces from some of the written records of ritual and

belief, the Kaula, and then Shakta and Tantra traditions, as well as contemporary ritual practices, the sacredness and inherent sexual power of women’s

bodies used to be revered and understood as a mimesis of natural order, however, it has been replaced by (but ultimately not lost and forgotten)

patriarchal moral order. For deeply embedded in the mandalic reality of Bhaktapur lays the matrifocal power of women and Goddess.