Indrayani Matrika Temple, Kathmandu © Laura Amazzone 2016

Introduction

In the Kathmandu Valley of Nepal, open shrines or pithas to eight goddesses known as the Asta Matrikas are located on the periphery of the city of

Bhaktapur. Other shrines to these goddesses situated within the boundaries of the city are known as “god-houses.” Each individual “house” holds a portable

image of one of the Matrikas and other accoutrements needed for her daily pujas by Tantric priests (Levy 1982, 231). Together these external and internal

shrines serve as focal points of worship during rite of passage celebrations and during the autumnal harvest festival, Mohani, and form a symbolic mandala

that influences the ritual and spatial organization of the city. In this essay I will explore how the geographical location of the shrines and other

dwelling places of the Matrikas reveal much about the multivalent functions of these goddesses. Specifically, I will show that the locations of the shrines

on the city’s periphery indicate that the Matrikas serve as divinities demarcating the boundaries between order and chaos, internal and external realms,

seen and unseen forces. An analysis of polarities found within Kaula, Hindu Tantric, and Shakta ideologies such as purity/impurity, chaos/order, sex/death,

sickness/health, menstruation/pregnancy further elucidates the many levels of meaning of the borderland status of the Matrikas. My central hypothesis is

that such contradictory tensions, particularly as they relate to sex, menstruation, pregnancy and death reveal vestiges of an older, matrifocal,

autochthonous tradition that has influenced the spatial layout of the city’s physical and cosmic boundaries. This study involves a hermeneutical analysis

of iconography, myth, local legends, history, anthropology and etymology from a feminist and heuristic perspective.

Goddess Durga & the Matrikas, Shobbhagawati Temple, Kathmandu © Laura Amazzone 2016

The Matrikas

The Matrikas are a collective of seven or eight goddesses, whose paradoxical natures express the interrelationship between the cyclical nature of women’s

bodies and perennial earth based rituals(Chamberlain, (now Amazzone) 2000, 24).[i] They are Mother Goddesses, yet not restricted to the procreative

implication of motherhood. The Matrikas are aspects of the Great Goddess in her full power and work together in collective form.[ii] Their anthropomorphic

representations found on temple struts, tymphaneums, and in shrines throughout the city depict them as creatures of paradox: either sensual or grotesque,

birth-givers or destroyers. In the Devi Mahatmya myth, they appear as aspects of the Great Goddess Durga’s Shakti power, which She calls forth to aid her

in the battle against the asuras, demons. They spring from Durga’s forehead riding animal mounts (goose, bull, tiger, etc.) in their most

terrifying forms and successfully restore equilibrium to the threatened cosmos.

Painted Manuscript of the Matrikas from a Devi Mahatmya text

Today, shrines to these eight goddesses are located on the periphery of Bhaktapur and guard the four cardinal directions and intermediary points. They are

known as Brahmani (east), Maheshvari (southeast), Kumari (south), Vaishnavi (southwest), Varahi (west), Indrani (northwest), Chamunda (north), and

Mahalakshmi (northeast). The placement of their shrines informs the processional route of the Mohani festival and will be discussed later. Some of their

names (Brahmani, Maheshvari, Indrani, Kumari) correspond to male gods within the Hindu pantheon, thus reflecting a brahmanization of what were likely

indigenous village deities that have been syncretized into this collective group. In fact, Bhaktapur is an amalgamation of early village settlements that

gradually grew into a city (Slusser 1982, 101), yet retained many of the older places of worship where cosmic forces conceived as mother goddesses were

generated, focused, and grounded.

Mahakali/Chamunda Matrika Shrine, Bhaktapur, Nepal ©Laura Amazzone 2016

Shakta, Kaula, or Tantra?

Given the rich ethnic, linguistic, and spiritual diversity of the Kathmandu Valley, one finds a tolerance of religious beliefs and practices within the

Hindu tradition resulting from centuries of assimilation of various ideologies, including those of the Kaula, Tantra and Shakta traditions, and Newari and

Tibetan Buddhism. Looking more closely at these traditions one may observe several sets of cultural and religious beliefs that have come together under the

larger umbrella of Hinduism in Bhaktapur. While Patan and Kathmandu have retained more Buddhist and mixed Buddhist and Hindu inclinations, respectively,

Bhaktapur tends to be more Hindu oriented (Slusser 1982, 103). I will refer here only to those traditions that are related to Hinduism.[iii] I am interested,

in particular, in various practices involving the Matrikas that are considered Tantric, Kaula or Shakta, and especially in the idea that ”the origin or

seeds of many traits, ideological or otherwise, can be traced to ancient, pre- Tantric, times” (Padoux 2002, 19). What these various traditions have in

common is an earth-based spiritual focus expressed through beliefs in the sacrality of local geography and female rite of passage rituals that are

intricately tied to elemental forces and the agricultural rice cycle.

Maheshwari Matrika Temple, Bhaktapur, Nepal. ©Laura Amazzone 2016

An analysis of this aspect of the Tantric, Kaula, and Shakta traditions offers insight into what ancient practices centering on this grouping of goddesses

may have entailed. It provides a lens through which to understand how the Matrikas were considered to be embedded in the landscape and how the arrangement

of their shrines influences the spatial and ritual organization of Bhaktapur. Before I proceed I will mention that what qualifies as Tantra is a huge and

controversial subject. There is thus no single definition of it (Urban, Harper, Padoux, White). The understanding of Tantra that I use as a basis for this

essay is closely aligned with David Gordon White’s view that Tantra is the “background against which Indian religious civilization has evolved” (White

2003, 3). I also rely on Andre’ Padoux’s definition of Tantra “not as a religion, but as various forms taken over the course of time outside the orthodox

Hindu and Buddhist traditions”(Padoux 2002, 23). These “forms” as expressed in the Shakta and Kaula traditions are what interest me and have influenced my

understanding of the role and function of the Matrikas and their relation to Bhaktapur geography. I now turn to some specific attributes of these

traditions that have informed this research.

Dakshinkali Temple, Kathmandu Valley, Nepal ©Laura Amazzone 2016

The Shakta tradition “views the divine as a female body of which women, earth, and the Goddess are but different manifestations” (Patel 1994, 69). In the

Shakta tradition, Shakti is the all- pervading dynamic energy of the universe. Perceived and personified as ultimately female, Shakti is

the divine consciousness behind the never-ending cycle of birth, life, and death. Therefore, the relationship between humans, vegetation, animals, spirits,

demons and divinities cannot be separated in the Shakta tradition, for they are all expressions of divine consciousness. We find a similar

conceptualization of the centrality of the female force behind all existence in the Kaula tradition and its concept of the inherent power of the “clan

fluid or nectar” within human women and divine female beings (White 2003, 11). It is clear that this conceptualization of the divine as female is very

ancient, as White notes, “Shakta is a relatively late technical term applied to these cults, scriptures, or persons associated with the worship of the

Goddess as Shakti: prior to the eleventh century, the operative term for the same was simply ‘Kula’ or ‘Kaula’: the term clan being applied implicitly and

exclusively to female lineages” (White 2003, 6).

Further consideration of the term kula is important to this study of the Matrikas and their relationship to the sacred landscape within and around

Bhaktapur. The primary sense of this term is “family, line, lineage (noble) race or clan,” while its non-technical meaning refers to “birds, quadrupeds,

and insects: a herd of buffalo, a troop of monkeys, a flock of birds, and a swarm of bees” (White 2003, 18). Likewise, iconographical representations and

mythical narrations of the Matrikas almost always depict them in a group[iv] with their distinguishing animal and bird mounts and faces. In this way, the

grouping of the Matrikas and their animal or bird vehicles corresponds to other groups of deities within the Kaula or Kula tradition. Kula deities, such as

the Yakshis, Grahanis, and in the medieval period, the Yoginis tend to be a hybridization of birds, plants, and animals with some human

characteristics (Ibid, 8). In the Kaula tradition the elemental nature of these goddesses was indeed rooted in the natural world.

Chamunda on the Taleju Temple door, Bhaktapur, Nepal ©Laura Amazzone 2016

Kaula practices include conducting rituals in charnel grounds, using alcohol and blood to feed and propitiate deities, inducing spirit possession in

ceremony, and employing transgressive sexual behavior as a means of achieving union with the divine. Padoux sees ritual elements such as transgression and

“erotic rites and sexo-yogic practices as antedating Tantra,” yet they still persist because they are a “universal category of human behavior.”(2002, 21).

Although these practices have continued through the ages, they are now only permissible within Tantric circles and, as we will see, during Mohani. As

Padoux notes, ritualized sexual practices allow for the body to be seen as “a structured receptacle of power and animated by that power and the

somato-cosmic vision upon which these practices are based”(Ibid). Originally, these practices equated the female body as a channel for female deities and

practitioners respected the inherent power within female sexual fluids and venerated the female body. Such practices utilized women’s bodies to achieve

certain powers (siddhis) and as a means to gain liberation (moksha). Significant to this discussion is the fact that such activity has

become peripheral to traditional religious practices because its involves elements now considered to be threatening and polluting to the civil order,

namely, functions related to the female body and intricately tied to the reality of human existence, i.e., menstruation, pregnancy, and sexuality. In this

conception, the “untamable” female body is equated with the “untamable” earth-as- mother, itself.

Birth-giving Earth Mother, Kirtipur, Nepal. ©Laura Amazzone 2016

In Bhaktapur today such practices take place through rituals centering on the Matrikas such as Mohani, rite of passage rituals, and secret Tantric rites.

All of them involve an attempt to master all levels of power—sexual, supernatural, spiritual, practical—allowing the individual to participate directly in

liminal realms of existence. Some of these normally secret rites (spirit possession, the use of alcohol and blood sacrifice) have become essential rites to

the Matrikas in the public Mohani harvest festival, thereby providing a ‘safe’ opportunity in which all of Bhaktapur’s citizens may annually participate in

otherwise threatening and feared realms of existence. These feared realms are often associated with places of power in the natural landscape, which

pre-date not only the boundaries of the city, but those practices which would be considered Tantra, Shakta, or Kaula.

The Matrikas Kaumari & Varahi, Kathmandu, Nepal ©Laura Amazzone 2016

Matrikas dancing and processing through the streets to ensure the coming agricultural

cycle and to bring blessings and protection to the community. ©Laura Amazzone 2016

Ancient Mother, Ancient Grandmother

Now that we have addressed elements relating to the Matrikas within the earliest recorded female-centered traditions, I would like to look at several

etymological references that point to a relationship with the word “Matrikas” and the earth. Throughout Nepal many places are referred to as maithan, or place of the mother (Ray 1973, 67). Similar to Matrikas, which means Mother goddesses, Mai is yet another

name for peripheral and chthonic goddesses. To the Nepalese, these goddesses’ powers are not only fearsome and terrible, but also fruitful and sustaining.

“This live spirit is indeed the fertile force which makes the land yield corn, roots and flowers, the herds to multiply and women to bring forth offspring.

The Nepalese know this force as Mai or Ajima” (Ibid). As Slusser notes, Mai and Ajima are two of the oldest names for

the Goddess in Nepal (1982, 107).

Aniconic Matrikas Shrine, Kathmandu, Nepal. ©Laura Amazzone 2016

The etymological significance of the word Matikas or Matr is also significant to this discussion. According to Panikkar, the word matr comes from the root ma, meaning to “measure across,” or “to be contained or comprised in.” It refers to “the one who has true

knowledge” (Pannikkar 1997, 1). This definition recalls the role of the Great Goddess who, by residing in the center of the universe (or microcosmic city

of Bhaktapur), can traverse the bounds of life and death (Chamberlain, (now Amazzone) 28, 2002). This meaning is strongly suggestive of the earth as

Mother, and encompasses tutelary elements that the Matrikas’ natures contain. Furthermore, it is only the Matrikas and related goddesses who can navigate

boundary places within and around the city such as crossroads, cremation grounds, and the city’s marked periphery without becoming afflicted by the powers

in these places.

Ajima and Mai (aniconic Matrika) shrine in Thamel,

Kathmandu ©Laura Amazzone 2016

The city of Bhaktapur is divided into a set of wards called gramas. Grama is a common Sanskrit and Nepali term for village (Levy 1992,

182). In some traditional town plans, “gramas were assigned to and named after presiding deities”(Dutt, 1925 in Levy 1992, 182). The Newari refer to the

smaller districts as twa and the larger ones as matwas, “the prefix ma deriving from a trunk of a tree of which the smaller neighborhood twas are branches” (Levy 1982, 183). Originally, Bhaktapur was a group of village settlements (now the various twas) that over the years

grew together into the city, Bhaktapur (Slusser 1982, 101). The use of the words grama and matwas recall a manifestation of the Goddess

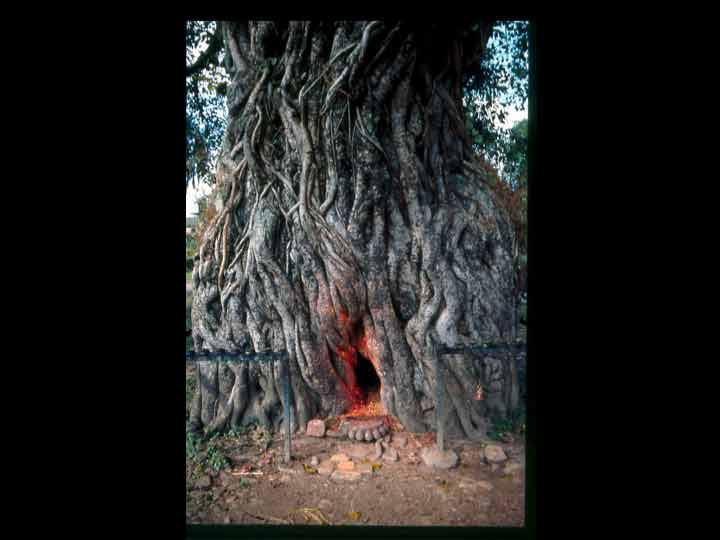

as tree who has spatially marked the bounds of village communities in villages in Nepal and parts of India, the Grama Devi.[v] Similar to the Matrika shrines

around the city, the Grama Devi is worshiped on the boundary of the village. She manifests in the form of a tree, marked with red vermilion powder by the

devotees or in a small, often hypaethral shrine on the outskirts of the village. Perhaps a foremother of the Matrikas, the Grama Devi is a tutelary deity

who protects the edge of the city as well as the center. She is, however, also deemed responsible for causing and curing childhood diseases such as small

pox, female illnesses, and stomach ailments such as cholera and dysentery (Gadon 2002, 34).

Grama Devi Shrine. ©Laura Amazzone 2016

In addition, we find a similar understanding of the Goddess’ paradoxical destructive and healing power in another manifestation of the Goddess, Ajima,

which means grandmother. Ajima seems to govern similar spheres of existence as the Matrikas. In Bhaktapur today, when children develop dysentery, offerings

to Ajima are either left at a place in the earth that is believed to house her or at another very common local of the Goddess, the crossroad. In Bhaktapur

each twa has at least one crossroad marked by an uncarved stone, if not more (Levy 1992, 193). Crossroads represent openings or gateways to other

worlds and today are feared and avoided unless offerings are left for the threshold goddesses and spirits who reside there. When trespassed without proper

ritual worship, the powers inherent in these places are believed to cause illness or even death. The Matrikas also carry this power to heal or inflict, in

fact, the Ajimas, Grama Devis, and Matrikas all seem to be different names for the same elemental forces that have been embedded in the natural landscape

for millennia. I contend that these various terms: grama, matwas, ajimas, maithan, and mai all refer to the earlier

understanding of earth as mother.

A Grama Devi shrine on the boundaries of the village of Sankhu, Nepal ©Laura Amazzone 2016

Gateway of Life and Death

When wandering through the streets of Bhaktapur, one will often come across natural stones either in circular groupings and smeared with red vermilion, or

a single uncarved stone that rests between the bricks of the road. I suggest that these groups of stones are an ancient prototype for collective forms of

the Goddess, the Matrikas, Nine Durgas, and even Yoginis. The single stones are called “Devi Stones”[vi] or “dhoka,” yet many inhabitants simply refer to them

as Ajima or as one of the Matrikas.[vii] Keeping in line with the characteristics of these goddesses, dhoka means gateway and can be interpreted in

several ways. First, this name reinforces the goddesses’ peripheral status as guardians of the city’s boundaries as well as guardians between the worlds of

spirit and human, order and chaos, illness and health, birth and death. Not only do pregnant women propitiate these goddesses before, during, and after

labor, but also place the after-birth, umbilical cords and used menstrual pads at these stones or crossroads within their twas, places where these

goddesses and ‘harmful’ spirits dwell (Levy 1982, 193).

Dhoka stone with offerings. Kathmandu, Nepal ©Laura Amazzone 2016

Second, these collective forms of the Goddess are also associated with cremation grounds, giving them governance over funerary practices and the gates of

death. We find iconographical evidence of the Matrikas’ association with death in depictions of Chamunda standing on a corpse. In addition, ritual

practices to the Matrikas (and Yoginis) locate them in cremation grounds.[viii] In Bhaktapur, three cremation grounds lie outside the city near the river (Levy

1992, 161). Although part of a natural process, death is considered polluting within orthodox tradition, and like birth, is women’s and the Matrikas’

domain.

Chamunda or Nardevi, Kathmandu, Nepal. ©Laura Amazzone 2016

It is interesting that much of what is considered polluting within orthodox tradition is, for the most part, related to the female body, and also to other

natural bodily processes: blood from pregnancy or menstruation, extramarital sex, excrement, urine, sexual body fluids, and death. Yet, because the power

of the Matrikas is real and embedded in the female body and natural environment, it cannot be totally denied. Therefore, I believe, practices in which

attempts are made to include, yet subdue and propitiate these goddesses take place.[ix] Padoux suggests that the reason behind many of the antinomian rituals

that occur within Tantric circles and the Mohani festival is so the inhabitants can participate in the “dark, chaotic, undisciplined, and very powerful

forces that are normally repressed and kept outside the pure, orderly circumscribed world of the Brahmin” (Padoux 2002, 21). In the “orderly, circumscribed

world of the Brahmin” such natural forces can be repressed, but not totally ignored. Although threatening, fear inducing, and ‘polluting’ these processes

are also recognized as vital and inseparable aspects of the natural cycle of existence and attempts are made to contain their inherent power.

As is evident from the worship and propitiation of the uncarved and simple dhoka stones, every part of the natural world is imbued with the

sacred, yet over time humans’ relationship to these sites has created the bounds within which they exist today. The Goddess has been worshiped in aniconic

form at crossroads, hilltops, rivers, cremation grounds, seas, mountains, forests, groves, and places marking the periphery of communities for millennia.[x]

It is exactly in such places that legend, myth, and human experience show is where the Matrikas, Mais and Ajimas dwell. Therefore, these primordial

goddesses ultimately cannot be separated from the natural landscape or elemental forces. It seems to not be coincidental that the city of Bhaktapur is

located on a hilltop, between two rivers, and at a location that once served as the major crossroads between Kathmandu and

Banepa (Slusser 1982, 12) suggesting the original conceptualization of city and environs ultimately as Goddess, Herself. We now turn to the structural and

conceptual layout of Bhaktapur as a mandala and the meaning of the Matrikas within the mandala.

Bhaktapur, City of Devotion: Matrikas as Mandalic Goddesses

The sacred geography of Bhaktapur marked by the outer shrines of the Asta Matrikas and the central temple to the Goddess Taleju (or Tripura Sundari [xi]) is

envisaged as a mandala, or “energy grid that represents the constant flow of divine and demonic, human and animal impulses in the universe, as they

interact in both constructive and destructive patterns”(White 2000, 9). Within the Hindu Tantric worldview, the profane cannot be separated from the sacred and all beings whether human or spirit; divine or demonic, mediate between various

levels of cosmic reality. In such a conception, the city becomes a “mesocosmic template” and thus “a graphic representation of the universe as a clan

(kula) of interrelated beings, an ‘embodied cosmos.’”(White 2003, 124).

UgraChandi Temple with the Matrikas. ©Laura Amazzone 2016

As we have seen, shrines and places in the earth sacred to female deities such as trees, certain stones, crossroads, cremation grounds, rivers, and so

forth, mark the boundaries of the mandala and separate the city into “inhabitable” and “uninhabitable” spheres. Within the mandala is a contained area

“within which ritual power and order is held and consecrated” (Levy, 1992, 153). For in Bhaktapur cosmology, chaotic, wild, and dangerous forces of nature

lie, for the most part, outside the borders. This is precisely where we find the Matrika shrines and the above-mentioned natural places. These goddesses,

themselves, embody the paradoxical natures of these forces that are threatening to structured moral order, yet as we have seen, are vital aspects of

cyclical existence and deeply imbued in the land. They must be propitiated in order to ensure order is maintained within the city. Consequently, the city

has been structured around the shrines in order to ensure the security of individuals, the districts or twas, and the city. The peripheral

location of the Matrika shrines reinforces these goddesses’ tutelary powers and ability to navigate between visible and invisible, ordered and chaotic

realms of existence.

An interesting point about the spatial organization of the shrines dedicated to the Matrikas is that they are not, in fact, placed in a geometric mandalic

pattern, nor do they encircle the actual physical boundary of the city. They are hypaethral and sunken, which suggests not only their antiquity, but also

their “ultimate chthonic origins” (Slusser 1982, 325). As Jayakar has noted, wherever physical features such as trees, stones, sunken shrines, and tirthas

(sacred places or crossings near ponds and rivers) are associated with goddesses, such sites are particularly old. At these sites worship may predate the

veneration of the goddesses themselves and may be rooted in earlier practices that centered on a conception of the land itself as sacred. Jayakar points

out that in these cases it is not necessarily the deity that maintains devotion and worship, but the holiness of a place:

The sacredness of sites survives the changing of the gods. A primordial sense of the sanctity of place, the sthala, and an ancient knowing of the

living, pervading essence of the divinity of the Earth Mother, establishes her worship (1989, 49).

In all likelihood, it is the persistence of ritual worship at these Matrika sites that influenced the delineation of today’s borders between the city and

the external seen and unseen worlds.[xii] Therefore, it is not any given geometrical arrangement that holds power and serves to maintain order there, but

rather the quality of the particular place that holds together the city’s order and is important (Auer and Gutschow 1974, 23).

Content for February 2016

If you value this knowledge please consider donating towards its production and dissemination worldwide in Sutra Journal. Be part of the effort to bring this knowledge to the world. Donations go towards the operating costs and promotion of the Journal.

If you value this knowledge please consider donating towards its production and dissemination worldwide in Sutra Journal. Be part of the effort to bring this knowledge to the world. Donations go towards the operating costs and promotion of the Journal.