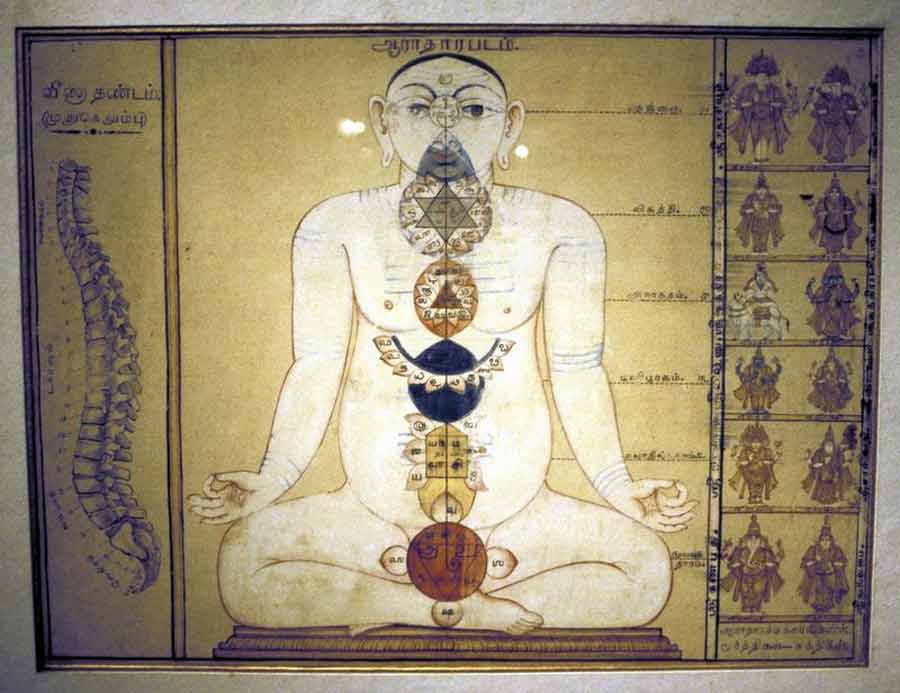

Six chakras, Tanjore, Tamil nadu cca. 1850.

Excerpts from the new translation of Haṭhayogapradīpikā.Published by Media Garuda @Kausthub Desikachar.

Introduction

The term Haṭhayoga needs no introduction today. Or does it?

Millions of people from every corner of the world claim that they practice or teach Haṭhayoga. But what is the true meaning of Haṭhayoga? What does it

constitute? And who are its eligible practitioners? Is it really a forceful kind of Yoga?

These and many other questions have remained unanswered ever since the term Haṭha hit the Yoga market. To clarify such questions and understand the

richness of its teachings, the best place to begin is the Haṭhayogapradīpikā, considered one of the most authoritative texts on Haṭhayoga.

Believed to be composed in the fourteenth century AD, the Haṭhayogapradīpikā is authored by the grand master Yogin Svātmārāma. He was not only an adept in

this field, but was also an expert in the deeper aspects of the Saṁskṛta language. The manner in which he presents such a rich teaching through the

powerful lyrics and beautiful poetry that constitute this text is a testimony to his proficiency.

He also comes from a long and illustrious lineage of teachers who were the architects of Haṭhayoga, at a time when India was in need of a social and

cultural renaissance. This group was considered revolutionary at the time, and hence was shrouded in controversy. So who are they?

Mahisamardini Durga, Parasuramesvara Temple,

Bhubaneswar,

cca 7th Century A.D

The Kāpālikas, or the Skull Men

The Kāpālikas are one of the two main sects of Śiva followers, who follow a non-Purāṇic or Tantric form of Śaivism. Some of their members were considered

to have written the Bhairava-tantras, including the subdivision called the Kaula-tantras.

They were in existence fairly early and were well known by the seventh century AD. Even the legendary Buddhist traveler Hiuen Tsang, who traveled through

India between 630-645 AD, saw them and described them as ‘wearer[s] of skulls.’ One of the characters in Bhavabhūti’s play, Mālatī-Mādhava, which was

composed in the eighth century, is a Kāpālika. According to the great Dvaita master, Madhvācārya, even Ādi Śaṅkara was in controversy

with the Kāpālikas. Ācāryas like Ānandagiri and Rāmānujācarya also talk about them, and the latter is believed to have viewed them as extreme in their

practices.

They are called Kāpālikas, literally meaning the ‘skull-men,’ because they carried a skull-topped staff and used human craniums as begging bowls. Differing

from the more respectable Brahmin householder of the Śaiva-siddhānta, the Kāpālika ascetic imitated his ferocious deity, Lord Śiva, covered himself in

ashes from the cremation ground, and propitiated his Gods with the supposedly impure substances of blood, meat, alcohol, urine and sexual fluids from

intercourse, unconstrained by caste restrictions. By flaunting such rules and going against Vedic injunctions, the Kāpālikas were considered impure by the

more orthodox Brahmins, and hence were considered a Tantric sect. Their main aim was spiritual power through evoking powerful deities, especially the

Goddesses.

Their divergence from the traditional and more orthodox social system can be attributed to various reasons.

Firstly, this was a time when Indian culture was becoming very sectarian and hence rife with conflicts. Many rules were also made that forbade a large and

significant portion of the population from practicing Yogic methods. For example, women and those from a lower caste were not really allowed to practice

the Aṣṭāṅga-yoga system propounded by Patañjali, owing to the use of Mantra in its practices. Mantra-s were a significant part of the classical

Aṣṭāṅga-yoga system. They were used in the practice of Āsana and Prāṇāyāma to measure duration of breath, and also formed an essential ingredient in the

meditative practices of Dhāraṇā, Dhyāna and Samādhi. So when Mantras became inaccessible to a significant portion of the population, then these other tools

also became unavailable to them.

Secondly, the traditional spiritual systems of practice became very structured and hierarchical, full of rules and regulations. Thus, in the perception of

the Skull-men, they became devoid of spontaneity, wisdom and intuition, all attributes of feminine energy. The Kāpālikas believed that the main purpose of

Yoga was to seek a harmony between the dual energies of masculine and feminine, and not just propagate the dominance of one. With their goal being to

create balance, they sought to honor the divine feminine, as well as the divine masculine. Despite honoring both forms of deities, they were primarily

known as the Goddess worshippers, because at that time the social norm was to honor only the masculine.

Thirdly, owing to the strict injunctions of the Brahmins, some articles were viewed as sacred, while others were not. And only these sacred articles were

approved to be used in worship, while others were rejected as unclean. The Kāpālikas were of the strong view that the divine sacred was everywhere in this

manifested universe, a view found even in the most important Upaniṣads. So the Kāpālikas, aggrieved by such biased perception of the more orthodox teachers

of the time, led the way by honoring the divine through supposedly impure substances such as blood, meat, alcohol, urine and sexual fluids from

intercourse.

Finally, they also disapproved of the traditional Brahmins of the time who aligned themselves with the ruling class, established themselves as Rājagurus

(teachers of Royalty), and lost themselves in affairs of state, rather than focusing on spiritual pursuits. The Kāpālikas were essentially ascetics, who

rejected material prosperity and pursued spiritual wealth instead, living a very simple lifestyle. For many their only material possessions were their

loincloth, their begging bowl and a staff.

This is why they were considered rebels, and were often cast out by the conventional society of the time. In the beginning they were left alone, as they

were considered to be no more than a bunch of eccentric practitioners. But this was not to last long, as they were not just uneducated freaks, but were all

very well versed in the traditional Śāstras.

Eventually, the immense popularity of their teachings would have threatened the Brahmin teachers, who often had the aid of the rulers as well. Hence it is

imaginable that they were sometimes hunted down, and so had to go underground for a while. This is perhaps one among many reasons why they repeatedly

express the idea that the Haṭhayoga teachings must be very carefully kept secret.

They had a very significant influence on Yoga, especially Haṭhayoga. Evidence of this can be found through texts such as Śivasaṁhitā and

Haṭhayogapradīpikā, among others, which list some of their so-called ‘eccentric’ practices. This apart, the main texts of their lineage, the

Bhairava-tantra and the Kaula-tantra, offer many Yogic practices as part of their teachings.

Bhairava-tantra is a key text of Kashmir Śaivism. It is presented as a discourse between Lord Śiva and his consort Śakti. The text talks about one hundred

and twelve meditation methods, known as Dhāraṇās, which include Prāṇāyāma, concentration on energy centres of the body, non-dual awareness, chanting,

visualization and contemplation through each of the senses. An important aspect discussed in these texts is the prerequisite to success

in any of the one hundred and twelve practices, which shows a clear understanding of how the method chosen must suit the practitioner.

Kaula or Kula describes a particular form of Hindu Tantrism, more associated with the Kāpālika sect of ascetics. Spiritual purity, sacrifice, freedom, the

spiritual master (Guru) and the heart are core concepts of the Kaula tradition. Similar to other Tantric schools, the Kaula-tantra adopts an approach of

positive affirmation, rather than prescribing self limitations and condemning certain actions. Thus it embraces concepts such as sexuality, love, social

life and artistic pursuits as important domains of spiritual evolution. The main approach of Kaula-tantra is practical methods for attaining enlightenment,

rather than merely engaging in complex philosophical debates. The main means are spiritual family, initiation into rituals, sexual rituals such as

Maithuna, spiritual alchemy, controlling energy through Mantra-s and other mystical methods, and the realization of individual and universal consciousness.

The Kaula lineage is closely linked to the Siddha and Nātha traditions. Their influence was therefore significant, because of the importance of the Nātha

lineage to the teachings of Yoga. It is highly possible that Svātmārāma and others in this lineage belonged to the Kaula tradition, and perhaps even to the

Kāpālika sect. This may be the reason for some of the mysterious practices that form part of texts such as Haṭhayogapradīpikā.

Throughout history, many conservative Yogins disapproved of their methods, and shied away from their practices. Yet the Kāpālikas have endured till the

current day. Visitors to Varanasi, the ancient and holy city on the banks of the river Ganga, can even now come face to face with such ascetics.

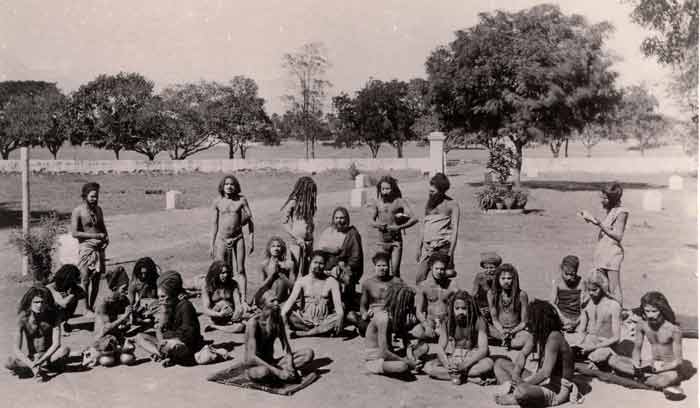

A group of sadhus gathered for a portrait; a photo from the 1890's.

The Lineage of Svātmārāma

Svātmārāma is believed to belong to the Nātha-sampradāya, an ancient lineage of spiritual masters, whose founding is often attributed to Lord Dattātreya,

an incarnation of all the three Hindu gods, Brahmā, Viṣṇu and Śiva. However, the establishment of the Nātha tradition as a distinct sect perhaps began

around the eighth century AD, with a simple fisherman called Matsyendranātha, who is also often known as Mīnanātha.

Matsyendranātha is often called the founding father of the Nātha tradition and hence is held in high esteem by followers of this lineage. Tradition relates

his story in the following manner. Long ago Lord Śiva was teaching Yoga to Girijā, another name for Pārvatī, on an island which he thought to be

uninhabited. A fish which was in the waters near the shore heard the teaching. Its mind became completely focused and its body motionless. Lord Śiva saw

how the fish was and assumed that it was due to hearing the teaching. He was kind and sprinkled sacred water on the fish. The fish thereby attained a

divine body and became a celestial being (siddha) called Matsyendranātha. Thus started the lineage of the Nātha tradition through Matsyendranātha.

Since the teachings actually originated from Lord Śiva, the Nātha-yogins call him Ādinātha, meaning the first Nātha. Matsyendranātha is acknowledged as his

first successor.

Matsyendranāthas two most important disciples were Cauraṅgī and the renowned Gorakṣanātha. It is believed that the latter eclipsed his master in importance

in many of the branches and sub-sects of the Nātha-sampradāya. It is the reason why even today, Gorakṣanātha is regarded by many as the most influential of

Nātha teachers. He is reputed to have written the first books dealing with Laya-yoga and the movement of the Kuṇḍalinī-śakti. Some regard him as the

original inventor of Haṭhayoga.

The Nātha-sampradāya does not recognize caste barriers, and their teachings were adopted by outcasts and kings alike. The heterodox Nātha tradition has

many sub-sects, but all honor Matsyendranātha and Gorakṣanātha as their originators and supreme Masters.

In the first chapter of Haṭhayogapradīpikā (verses I.5-I.9), Svātmārāma acknowledges that he belongs to this illustrious lineage of teachings and honors

all the masters who preceded him.

Is Haṭhayogapradīpikā the only Haṭhayoga text?

It is certainly not the only text, nor is it the last word on Haṭhayoga. There are several other Haṭhayoga texts, which not only share common areas of

teaching, but also have their own unique practices that are not part of the Haṭhayogapradīpikā. Many of these texts are quoted by the commentator

Brahmānanda, in explaining some finer aspects of the teachings.

In his text, Yogin Svātmārāma has given practices following his own lineage. But the larger discipline of Haṭhayoga also has varying opinions and

practices. For example, the Śivasaṁhitā describes Mantra-yoga, Chāyā-puruṣa-sādhana, and Cakra-dhyāna as additional practices.

Gorakṣa-paddhati, another Haṭhayoga text, describes Ajapa-sādhana, which many Nātha sects regard as an important practice.

It is also noteworthy that some practices from the Haṭhayogapradīpikā do not match with practices appearing with the same name in some other texts. For

example, the techniques of Vajroḷī-mudrā, Amaroḷī-mudrā and Sahajoḷī-mudrā from the Haṭhayogapradīpikā are different from those explained in the

Śivasaṁhitā and the Gheraṇḍasaṁhitā. The same is true for Śakticalana-mudrā.

So it can be concluded that Svātmārāma has presented the techniques of his own immediate Guru-paramparā or lineage, and that other schools of Haṭhayoga

would have had their own variations of techniques.

Some verses of Haṭhayogapradīpikā seem to have come from some other Āgama texts. Perhaps Svātmārāma used several other texts as references for his work,

and just quoted them in the appropriate places as part of the main text.

What is also very significant is that the Nātha-sampradāya is mainly a Śaiva sect. However, nowhere in the Haṭhayogapradīpikā are the basic philosophical

tenets of the Śaiva system described in detail. Instead it focuses primarily on the technical aspects of Haṭhayoga, thus making the text neutral and

universal. It could be this aspect of this work that made it so popular and allowed it to be embraced by many, even those who did not belong to the Śaiva

sects. A classic case is that of the legendary modern day master Ācārya T Krishnamacharya, who belonged to the Vaiṣṇava sect, but still regarded the

Haṭhayogapradīpikā as a very important Yogic text.

Shiva crushes Tripurasura, Karnataka. cca. 11-14th Century AD.

Brahmānanda - The Commentator

The Jyotsnā commentary of Brahmānanda is one of the most respected commentaries on the Haṭhayogapradīpikā. The fact that there are no other well-known

classical commentaries on this text underlines its importance. Its significance is also revealed by other aspects of this prose. Not only does it highlight

the commentator’s authority on the subject of Haṭhayoga, it also demonstrates his expertise in various allied subjects and classical texts that were in

vogue at his time.

However, very little is known about him and his personal life. There are two possible reasons. One is that he, like many of the traditional Nātha

practitioners, chose to remain hidden among the public as a wandering ascetic, so that his focus was more on spiritual evolution than

fame. Secondly, it could also be that, owing to his own humility, like many of the great masters of the time, he chose not to give any personal information

in his work, and rather let his work speak of him. A general picture of him can hence only be made through snippets of information offered here and there.

He is thought to have lived during the eighteenth century and was a contemporary, and more likely a student, of Meruśāstrī. We can come to this conclusion

as he quotes when beginning the commentary to the Haṭhayogapradīpikā.

Meruśāstrī or Meruśāstrī Godbole, as he was known during his time, was a well-known scholar, who was originally from Pune, but is believed to have lived in

Audumbar, where he is said to have met Brahmānanda. It is well known that Meruśāstrī is the author of a text titled Vākyavṛtti, a commentary on the

Tarka-saṁàgraha, a treatise on the Nyāya-śāstra. Some scholars are of the view that the Jyotsnā commentary was written well before the Vākyavṛtti.

It is very clear from the first section of the Jyotsnā commentary, that Brahmānanda acknowledges the help of Meruśāstrī in presenting the commentary to the

Haṭhayogapradīpikā, and therefore acknowledges him as his teacher.

Jyotsnā, which literally means moonlight, true to its name, provides a gentle and comforting understanding of the powerful and profound teachings of the

Haṭhayogapradīpikā.

The special view on Īśvara

Earlier it was briefly mentioned that teachers like Ādi Śaṅkara had conflicting views with the Kāpālikas. This point needs further elaboration. Ādi Śaṅkara

is perhaps the most renowned Śaiva Ācārya, and the main proponent of the Advaita philosophy. In this philosophy a few fundamental tenets are strongly

advocated, including the very strong idea that the divine is without form or attributes (nirguṇa-brahman). This is one of the defining features of

Advaita-vedānta philosophy.

However, in explaining Śāmbhavī-mudrā, in the fourth chapter (IV.37), Svātmārāma and the commentator insist that the meditation must be on Īśvara with

attributes (saguṇa-brahman). Thus it becomes clear that the Haṭhayoga text does not conform to the Advaita-vedānta philosophy, and hence must definitely

not be understood as non-dual in nature.

This is perhaps another key reason why Haṭhayogapradīpikā gained immense popularity among practitioners, especially those belonging to the Vaiñṇava

traditions. Despite their differences, Vaiñṇavas definitely held the view that Īśvara was full of auspicious attributes, and hence this made it easier for

them to embrace the teachings propagated by the Haṭhayogapradīpikā. This is an important reason why an Ācārya like T Krishnamacharya whole-heartedly

supported the teachings of this text and taught it to his key students.

Parallels may be drawn with other Asian systems such as Tai-Chi or Qi-gong, which also speak about the efficient movement of energy.

Hence the modern idea that Haṭhayoga is mainly the strong practice of Āsana is clearly flawed, and one that comes from a very superficial understanding of

the subject matter.

Is it really forceful Yoga?

The most misunderstood aspect of Haṭhayoga is that it is thought of as a forceful form of Yoga. Because of this, many Yoga traditions insist on students

forcing themselves into difficult Yogic postures to achieve the so-called ‘perfect form.’ However, this is more a case of meaning being ‘lost in

translation’, rather than it being the actual message behind the teachings. The dictionary definitely lists one of the meanings of the word ‘haṭha’ as

force, and literalists may hang on to this word to justify this point. However, there is subtlety and sophistication to the interpretation of this very

special word.

The misinterpretation comes from the use of the word ‘haṭhāt’ by the text in a few instances especially in the third chapter (III.51, III.105, and

III.111). In all these places, when the commentator’s notes are read carefully, it becomes clear that the force they are talking about is the force of

Prāṇa, not physical force. And the force of Prāṇa comes, not from forcing ourselves, but through its careful harnessing, which is achieved by systematic

practice done over a long period of time, under the capable guidance of a teacher.

The confusion is made stronger because in many instances the word for Prāṇa used in the text is Śakti. Śakti is a synonym for Prāṇa, but it also means

strength or force. Hence by choosing the wrong meaning of a certain word, the interpretation of the teaching can be greatly misunderstood.

This is the case with many modern day practitioners of Haṭhayoga, who push themselves or their students into difficult postures through the use of physical

force. This comes from a barbaric misinterpretation of subtle teachings, which not only harms the practitioners, but essentially destroys the sanctity of

these timeless teachings.

The reader is asked to note carefully the repeated reminders of both author and commentator that one must practice within one’s capacity (yathāśakti) at

that moment in order to eventually master the practices.

Read in Part Two: What is Hatha Yoga, The Kundalini Conundrum and more….