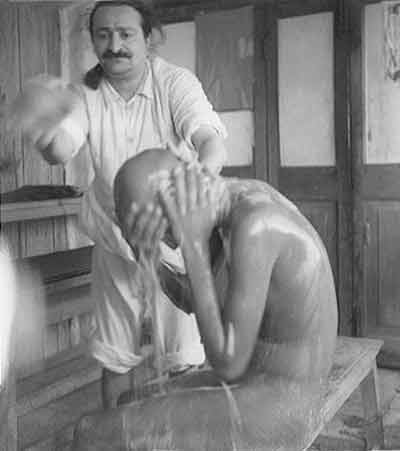

Meher Baba washing the feet of the poor in India

Author’s Note:

Meher Baba’s work with India’s masts (‘‘God-intoxicated ones’’) in the 1920s–40s helped inspire Laing’s ‘‘anti-psychiatry’’ in the 1960s of a

medication-free kindness in treating the mentally-ill and predates by decades the concept of ‘‘spiritual emergence’’ developed by Sannella, Perry, Grof and

Grof in the 1970s and thereafter. His concept of the salik conveys the essence of Wilber’s ‘‘pre-trans fallacy’’ (mistaking enlightenment for an immature

forerunner). His view of ‘‘God intoxication’’ appears to be a culturally-dependent, extreme instance of a potentially non-pathological ‘‘Depersonalization/

Dissociation’’ as noted in the DSM-IV-R. From Meher Baba’s saintly perception of an essential holiness (awe- and love-inspiring nature) of consciousness

itself, I derive inspiration for a psychotherapy of ‘‘clinical forms of love.’’ I also introduce the concept of ‘‘spiritual surpass,’’ problems attendant

to successful spiritual maturation, in contrast to ‘‘spiritual bypass,’’ problems related to egoic immaturity.

Introduction

Contemporary issues of interest and concern to transpersonal psychology have antecedents in the 1920s–1940s in the work of Meher Baba in India. He helped

inspire the work of R.D. Laing in the 1960s (1964 with Esterson, 1965, 1970), predates the work of Sannella (1977/1987), Perry (1974), and the Grofs (1989,

1990) on ‘‘spiritual emergence,’’ and foreshadowed Wilber’s ‘‘pre-trans fallacy’’ (Wilber, 1980a, 1980b, 1995). This article offers historical background

regarding these topics, so central in the early development of transpersonal psychology, and outlines further innovations in clinical practices inspired by

Meher Baba’s pioneering vision.

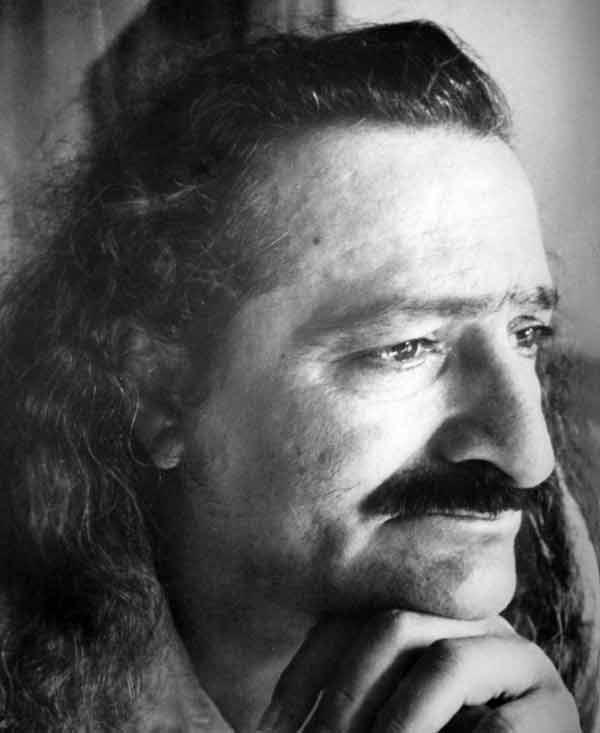

Meher Baba 1941

Meher Baba: Biographical Sketch

At 19 years of age, Meher Baba (nee Merwam Sheriar Irani, 1894–1969) received a kiss on his forehead from the highly venerated Muslim woman, Hazrat Babajan

(alleged to be 122 years old at the time), and then kissed her hands. That evening, he entered an altered state of blissful, ‘‘electrified’’ consciousness

wherein he did not sleep or eat for nine months. ‘‘I had no consciousness of my body, or of anything else. I roamed about taking no food ... [and

experienced] Divine Bliss’’ (Ramakrishnan, 1995, p. 120). For the next seven years, he remained largely dysfunctional, beyond the reach of doctors and only

gradually regaining normal capacities, but conveying to many around him various saintly attributes for the rest of his life. He remained in silence after

1925, made several teaching tours throughout Europe and America and drew a following of many hundreds of thousands worldwide who believed him to be an

avatar, the most mature of saints in the Indian terminology.

Meher Baba spent some sixteen years ministering to ‘‘God-intoxicated’’ masts (as he called certain catatonic-like individuals whom he asserted where not

mentally ill, but were wholly stunned by the awesome infinity of consciousness) and the mentally-ill (those whom he felt were specifically struggling with

mental disorders) throughout India in the 1930s and 40s. He would personally wash, feed, cater to their every whim, look lovingly into their eyes or cradle

them in his arms–some unbathed for decades, many apparently autistic or catatonic. As a result of such care, many became socially engaging, if also

somewhat eccentric persons, while others appeared only minimally changed, as documented in great detail in Donkin’s The Wayfarers (2002). His

elaborate map of consciousness (formulated in the 1930s and 40s), a unique amalgam of Sufi, Vedic, and Yogic terminology, can be found in his Discourses (1967/2002) and God Speaks (1955/2001).

Introducing Admiration and Other ‘‘Clinical Forms Of Love’’ in Psychotherapy

Surely, most people who take up the century-old profession of Clinical Psychology/ Psychiatry are manifesting by this career choice their caring love for

others who are suffering emotionally, mentally, or, we might even say they are suffering ‘‘spiritually.’’[i]

The conventional education to become a licensed psychotherapist or psychiatrist entails primarily intellectual study and training in clinical techniques

based in contemporary psychological theories. Nowadays, meditation techniques and Yoga might even be used as adjunct treatments.

Aspiring psychotherapists may also undergo training analyses wherein they examine their motivation for entering this profession. This involves a

psychodynamic review of childhood and other experiences, traumas, and pressures that may have informed their decision to become a psychotherapist. The

concept of ‘‘love’’ will likely be analyzed in reference to erotic, oedipal, compensatory, dependent, and other pathological/counter-transferential

potentials.

The neophyte therapist’s caring love for patients will be honed to a singular mode of compassionate listening attuned to patient suffering and a general

empathic reflective responsiveness (‘‘mirroring’’) to patient reported experiences. Much focus will be on ‘‘shadow’’ emotions such as jealousy, resentment,

envy, anger, etc., to make such feelings tolerable, ‘‘conscious,’’ and traceable to their immediate cause and other more distant and childhood influences.

But what about the caring love for others, simply and directly, that brought these people into the profession? What about the matter of ‘‘love for others’’

itself, as Meher Baba and numerous other saints have taught? How can someone be trained to become an ‘‘expert’’ in ‘‘clinical expressions of love’’ itself

(not just in the giving of various analytic or psychodynamic interpretations, psychopathological diagnoses, behavioral strategies, the ‘‘firm love’’ of

‘‘maintaining clear boundaries,’’ or even the warm empathy and compassion for traumas and disappointments)? I take this to include apt verbal expressions

of admiration, delight, appreciation, gratitude, and kindness, yet taken far beyond the laymen’s level of precision, detail, and therapeutic intent and

follow-up.[ii]

The aptness therapeutically of such verbally expressed ‘‘clinical love’’ would be a matter of any observable contribution to the patient’s emotional

maturation, happiness, creativity, and improved relationships with others. Such ‘‘client gratification’’ (positive interventions that psychoanalysis warns

against), however, need not result in an infantilizing ‘‘dependency’’ (on the ‘‘loving’’ therapist) that has long been presumed by psychoanalytic theory.

For, according to the teachings of numerous world religions and the Western Romantic tradition, love is a fundamental characteristic of consciousness. As

the smiles, blushes, mild tearing-up and other bodily radiances (and scientific studies of their physiology) suggest, such love received has a positive

effect upon physical health, as folk wisdom worldwide declares without much ado.[iii]

Detail and Duration: Refining Admiration for Psychotherapeutic Ends

Although what distinguishes ‘‘clinical admiration’’ from ordinary compliment giving is primarily a matter of duration (from five to thirty minutes per

therapy hour) and detailed focus upon character traits and actions, the effects can rival those of mood elevating medications. (This is my opinion gathered

over the past thirty years with over two thousand patients where a ‘‘critical dosage’’ of appreciative words is required to alter the patient’s

biochemistry, such that patient creativity and self sufficiency are activated.) While ‘‘positive reinforcements’’ of various sorts are a staple of many

modes of psychotherapy, such sustained ‘‘clinical admiration’’ is otherwise rare.

The duration of such admiration plays upon the many details of the patient’s life that appear admirable to the so-trained therapist. This can include the

courageous way he or she suffers and longs for improvements teetering within his or her frustrations, the power of his or her erstwhile hopefulness now

contorted within angered disappointment, the sheer perseverance involved in traveling to the session, the glow of hope on his or her face, his or her

clarity in describing the problem, his or her quavering idealism, intelligence, kindness, humor, and so forth. It is the unusually long duration and

detailed richness of such compliments that (perhaps ironically) helps ensure against fostering dependency of the patient upon the therapist.

Meher Baba, 1941

Avoiding Dependency

The patient receives ‘‘enough’’ admiration (to the point of blushing, which indicates the compliment has struck ‘‘to the quick’’) to nourish him into

further self-appreciation and healthy interdependence. This would include the improved ability to receive and give admiration and gratitude with others

outside of the therapeutic relationship, to share and compromise preferences and desires, and to apologize and forgive self and others. Arguably, it could

be the conventional psychoanalytically-oriented therapies that foster dependency upon the clinician by eschewing nourishing the patient in the ways I have

just described (in the hopes of inducing a weaning ‘‘individuation’’ based upon ‘‘non-gratification’’). Regarding Meher Baba’s work with masts, Donkin

states,

Every day when [Meher] Baba came, it was as if a brilliant flame were kindled in the depths of Mohammed’s [a seemingly catatonic God-intoxicated mast]

being, that for a moment lit up the dark and tangled ways, and slowly these fleeting moments of inner radiance have grown more and more sustained, so that

Mohammed today now radiates something unusual and charming. (Donkin, [1948/2002], p.48, with photographs)

Broadening the Client Context

If the patient is also a parent, the therapist can admire him for all the efforts to clothe, feed, ensure the safety of, be affectionate toward, and teach

his child. Moreover, the more difficult the parenting task (due to illnesses, poverty, and juvenile delinquency), the greater would be the therapist’s

admiration. Thus, too, the greater its ‘‘redemptive power’’ in reviving the nobility of the patient’s long-suffering parental efforts that may have been

crushed into resentment via a lack of adequate admiration. Indeed, in the case of juvenile offenders, such parents feed upon only shame and disappointment

regarding their child, particularly in conversation with school authorities and police. Whatever noble struggle the juvenile may be going through, too, is

lost in the focus upon his delinquency only. It is the extraordinary ability to discern the nobility of any struggle, no matter how dark, mundane, or

subtle, which is to be cultivated in (spiritually-oriented) clinicians, as inspired by Meher Baba and many other saints. Likewise are the powerful

‘‘redemptive’’ effects of the detailed, prolonged praising of marital partners locked in cycles of fighting and harshness who now admirably seek help in

establishing a creative and loving marriage and family life. What courage, what optimism lives beneath such anguish?

Mundane Simplicity Can Belie Therapeutic Potency

I first implemented such discernment in 1973 as the probation officer for a juvenile offender awaiting being sentenced as he was casually handed a cigarette

from his father. I merely asked the son to thank his father, which he did. Then, unexpectedly, the father began to cry, and then the son, apparently in the

poignancy of the long-lost intimacy that just then emerged, triggered by the simple, respectful expression of thanks at this especially despairing time.

Yet, without my suggestion to give thanks, this moment of intimacy seems unlikely to have occurred. And without asking the father and son to look at one

another, the visual impact of their shared intimacy would not have become a memory that was to serve them for many years, as an often obscured reminder of

their bond of love.

When I said,

‘‘This is the bond of father and son, both of you coming to a probation officer’s [office] together—not breaking the bond between the two of you out of

frustration, or shame—even at a time like this.

Not every Dad will come to his son’s P.O. with him at a time like this, and not every son will allow for his father to come with him. A bond twisted again

and again, but not broken.’’

As Meher Baba notes,

The life of the spirit is an unceasing manifestation of divine love and spiritual understanding, and both these aspects of divinity are unrestricted in

their universality and unchallengeable in their inclusiveness. Thus, divine love does not require any special type of context for making itself felt. It

need not await some rare moments for its expression, nor is it on the lookout for somber situations that savor of special sanctity. It discovers its

expression in every incident and situation that might be passed over by an unenlightened person as too insignificant to deserve attention.

If there is lack of happiness or beauty or goodness in those by whom a Perfect Master is surrounded, these very things become for him the opportunity to

shower his divine love on them and to redeem them from the state of material or spiritual poverty. His everyday responses to his worldly environment become

expressions of dynamic and creative divinity, which spreads itself and spiritualizes everything he puts his mind to. (Baba, 1995, p. 87)

Also to be included in such therapeutic love would be the therapist’s timely expressions of being inspired by the patient’s courage, honesty, integrity,

perseverance, and hopefulness. And, given that people live in relationship with others, such a ‘‘soteriological’’ (spiritually healing, per the Greek, soterios) therapy would invite these others into the treatment sessions of any individual, whenever possible.

Admiration in Family Therapy

In such family therapy sessions, the therapist readily conveys his admiration for family hopefulness, courage, etc., to all present and helps the entire

family to share in the experience of being so admired. Each one smiles upon receiving a compliment, causing others to smile shyly. Creative aspirations

awaken as the ‘‘spiritual biochemistry’’ of family members is uplifted, visible in the glow on the faces and eyes of each. Cynicism gives way to humor,

hope, apologies, forgiveness, pledges to improve relationships and brainstorming ways to do so. The therapist constantly points out the admirable courage

at each juncture, often taking five to ten minutes to do so, and has family members make eye contact at numerous poignant moments, creating visual memories

that will serve as reminders of hope and love.

[Therapist to a 17 year-old daughter hatefully rejecting her stepfather] ‘‘You say you hate Bob, but I’ll tell you something, you came here so I could help

you learn a deeper power than hate and that is, as corny as it sounds, love—to learn how to invite him into your new family, to find that creativity in

yourself that won’t just help him to be like a dad to you and give the both of you that chance, but that will change the course of your life. You know

about the power of hate and destruction out of anger but this other power is what you have, just by coming here with your Mom, the courage to let a

stranger, me, tell you about the love that is in your heart that you really want to find out about that you already know about with your friends and sister

whom you would never let down—but now, even with Bob. It [this creativity] will blow your mind. It will make what you say now is ‘‘impossible’’ become not

just possible, but will be a power in you that you can turn to years from now, in your own marriage with your husband or your kids—instead of rejection or

calling it quits, you will have the confidence to want to work it out. The minute before you tap this power, you will think it’s stupid or not right to do

because you are outraged or whatever. But when you remember how you gave your poor old stepfather, Bob, another chance and invited him into the family,

then you will want to do this same kind of thing again and again. Do you see that your Mother can see this in you, right now? You can see it in her right

now, too. This is why we are here, why else did you think? And that is what makes you such a great person, and why all your friends look up to you, and why

I admire you so much, you have the power to help create a whole new future with your Mother and Bob and his kids and your sister. They all want that kind

of future together and I admire you for even listening to me.

Daughter: ‘‘...Maybe ...’’

Via stories, via teasing out the most hopeful scenarios and desires, or foreshadowing of the creative future before them, the therapist inspires the

family, while the sheer duration of the admiration further stabilizes the transformed ‘‘spiritual biochemistry’’ of the family.

More Deeply Seeing and Sharing Admiration

Sustained eye contact is encouraged by the therapist at particularly poignant moments of contrition, forgiveness, or admiration–given and received. In the

few extra seconds of eye contact supported by the therapist’s requests, ‘‘exponentially’’ deeper degrees of love, connection, and reconciliation occur.

Family members literally ‘‘see’’ qualities in each other that otherwise would have receded into the unnoticed periphery. These deepened sightings yield

facial reactions in each partner that trigger even deeper moods of love, blushing, and openness that,when witnessed, trigger even deeper moods of the same,

that trigger even deeper moods (thus, my metaphor of an ‘‘exponential’’ deepening).

Therapist: Take a long look at one another [embattled husband and wife] and see the commitment between the two of you that is bigger than all your

differences, to your marriage and to your children, that is making you become the kind of mature person that you have always wanted to be, and see that is

what is happening to your spouse as well. See that glow? It makes you slightly shy to believe what I am saying, although it is the simple truth. And that

glow you see in each other is also about you—can you let that in? See, now it deepens even more: that is how nourishing you are to one another, your pride

in one another and in yourself and, really, what you have been starving—not just to receive—but to give to one another, just as well. What adjectives can

you each use to describe the beauty you see in each other’s face now, and now, and now?

Solving Problems in an Admiration-Rich Environment

Herein lies the therapist’s sustained attentiveness in helping to create momentarily and repeatedly certain ideal interactions that family members may have

longed for, but have previously been unable to manifest due largely to their emotionally malnourished status that lacks the creativity to do much more than complain.

But after the therapist has doggedly fanned the slightest spark of good-will into a faint flame, the members get the nourishment, their

‘‘spiritual-biochemistry’’ shifts their embodied conditions toward greater creative thought-production and subjective emotional states. It is within this

heightened optimism, creativity, and connection that substantive problems are addressed, for now there is ample creativity and felt-reunion to motivate the

requisite commitment necessary for more long-term problem-solving and growth.

Recovering Disappointed Love Hidden Within Angry Verbiage

Thus, too, the clinician/mediator must be skilled in disentangling the primordial hopes for (sharing) love from the cantankerous, even vituperatively

vengeful, language (and love-starved logic) that can spin on and on in the patient’s mind and in their conversations with others (indeed, in the actions

between hostile nations for centuries on end). For example, ‘‘I hate you, you abusive bastard!’’ is to be understood as ‘‘I am starved to the point of

emotionally emaciated desperation for the want of sharing love with you, and I now show you how important your love is to me via my upset at not sharing it

with you, thus starving you into an emaciated condition, so you will really understand what the starvation is like in me that the absence of your

so-valued-by-me love has engendered.’’

From the soteriological perspective, to not share love with others is to be deprived of sharing one’s essential nature with others and experiencing oneself

thusly. Thus, experiences of abuse that result in a reluctance to express love are doubly injurious, for expressing positive feelings, not just receiving

them, is herein considered a kind of ‘‘need.’’ Thus, too, clients ‘‘need’’ to express their positive feelings to and about their therapists, and in seeing

the so-produced glow on their therapist’s face, they come to learn that their expressions have positive impact in the world, and that they are in

possession of such nourishing powers.

Linguistic Concerns in Reviving Hopefulness

Psycho-linguistically, client complaints employing negated verbs, ‘‘I don’t feel any love for anyone!’’ can be assisted by converting the sentence to its

implied positive expression as a type of bhakti-like longing, ‘‘I wish I could feel some love!’’ Psycho-linguistically, the subject of the latter sentence

(the patient) is carried forth by the affirmative verb of wishing, while the negated verb form traps the subject in a verb whose negation impedes him from

‘‘going toward’’ his greatest hope. Indeed, the Bhakti tradition teaches that longing is the central mode of maturing one’s capability to love. And, as

Buddhist epistemology teaches, name and form go together. Thus, linguistic shifts open up new possibilities for perception, thought and action, in keeping

with Wittgenstein’s potent aphorism that languages are ‘‘forms of life,’’ and each shift in wording creates a changed world. [iv]

Meher Baba washing a mast 1946

Serving Others as Therapy

While therapists might not be awakened saints, they might well be trained to some degree in such saintly ways of perceiving and speaking. Indeed, we must

wonder at the possible therapeutic effect should a clinician join a hospital orderly in the following acts of loving service to his patients, as Donkin

notes of Meher Baba:

Baba’s work—his visible and external work, was to shave, bathe, clothe, and feed each inmate [mast living in his ashram], as soon as he arrived, and each

day to scour the latrine, and to bathe and sit in seclusion with a certain number of the old inmates. In this way he would throw every ounce of energy into

doing every sort of menial task .... (Donkin 1948/2002, p. 96)

All that Baba says about his work with the God-mad and masts is that he loves them and they love him; that he helps them and they help him. (Donkin 1948/

2002, p. 97)

As Meher Baba’s statement implies, such caring love would be beneficial to patient and therapist alike. Perhaps the granted mutuality of giving and

receiving is yet another therapeutic benefit for the patient who thus comes to understand himself as a source, not just a deprived recipient, of valued and

nourishing love.

Spiritual ‘‘Surpass’’: Awakening to the (Awe of) Infinite Consciousness:

Problems Inherent to Spiritual Growth

The concept of ‘‘spiritual bypass’’ locates problems of spiritual development in egoic immaturity or unresolved past trauma. Yet, there is also the

possibility that spiritual awakening can be inherently challenging, even for the most mature or untraumatized individuals (even those who have ostensibly

resolved all ‘‘bypass’’ issues). Indeed, ‘‘awakening’’ might bequest the awakened one not only an inner peace, profoundly present-centered attention, and

resolution of bypass issues, but also new problems attendant to increased faith, love, sense of responsibility, powers of judgment and empathic sensitivity

to ever-expanding spheres of world-suffering, etc. This has, in fact, been the case with numerous historical saints, including Meher Baba,Christ, Saint

John of the Cross, Socrates, Dalai Lama, et al. Thus, an assessment of ‘‘spiritual surpass,’’not just ‘‘bypass,’’ deserves to be considered. Spiritual

surpass issues would include:

· Self-compelled desires for heightened ethical behavior, including those related to the ‘‘love ethic’’

· Emergent moods of both intensive confidence and humility which engender creative actions, but devoid of egotistical strivings

· Communication struggles regarding ‘‘ineffable’’ experience

· The emergence of yogic powers of shaktipat (energetic transmission to others)

· Anguish resulting from sensitized empathy for suffering

· The question of assuming a public role of ‘‘spiritual teacher’’ (or not)

· Assessing the limits, as well as the breadth, of one’s spiritual knowledge and awakened state

· The matter of whom to consult for help, once one has ‘‘gone public’’ as a ‘‘self-realized being.’’

DSMV-I R V62.89 Code and Spiritual Surpass

Thus, I suggest that the V Code 62.89 in the DSM-IV R should be expanded to include spiritual problems that emerge, not only in ‘‘troubling

times,’’ but also in the wake of epiphanies, satori and other purely positive, revelatory events of awakening. And, given that the clinical archive has no

record of the psychotherapy of a contemporary person who ‘‘becomes enlightened,’’ those clinicians who consult that record will find no basis to assess

whether a specific client fits the profile of such a one. Since no such profile exists for her to make such an assessment, she could very likely (unwittingly)

mis-assess the progressive surpass issues of an awakening client for regressive bypass issues in need of ‘‘much therapeutic work’’—particularly those

trained in highly retrospective psychoanalytic or psychodynamic methods. And, who is there to tell a client that he may have exceeded the level of

awakening or clinical training of his own therapist?

Clinical Discernment of Surpass Emotions and the ‘‘Peter Principle’’

Given that (even) transpersonal therapists are rarely trained, for example, in discerning the difference between ‘‘awe (of inner infinity)’’ and

‘‘anxiety,’’ or between ‘‘moods of surrender’’ and ‘‘depression,’’ the tinglings of awakened prana (pranotthana) and those of a

‘‘repressed body-memory’’ or between ‘‘transcendence of sexual desire’’ and ‘‘repressed sexual interest,’’ how can such clinicians hazard making

assessments? Are the former terms even studied to the depth of, say, shame or grief or anger, by transpersonal therapists? And, as the historical record of

saints shows, in vivo, awe and anxiety, surrender and depression, etc., are typically intermingled with one another. Indeed, the greater the awakening, the

greater such intermingling of moods, for typically such saints move into ever-higher levels of responsibility, where the ‘‘Peter Principle’’ obtains. [v]

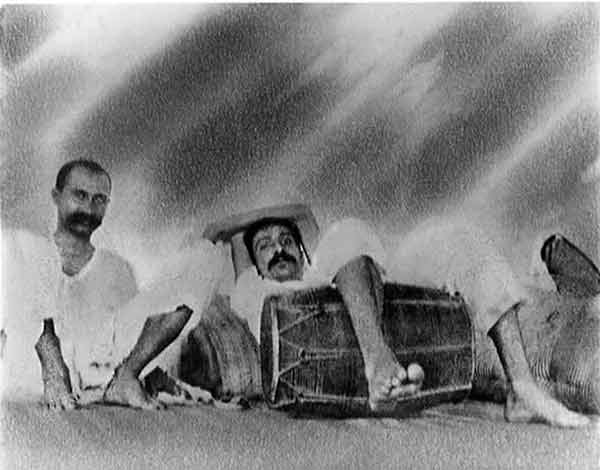

Krishna shows Arjuna his universal form (bazaar art by C. Konddiah Raja

Overwhelming Awe of Sheer Consciousness

Consider the definition of consciousness-knowing-itself as subjective infinity made by Ludwig Feuerbach, arguably the first Western ‘‘spiritual

psychologist,’’

Consciousness, in the strict or proper sense, is identical with consciousness of the infinite; a limited consciousness is no consciousness; consciousness is

essentially infinite in its nature. The consciousness of the infinite is nothing else than the consciousness of the infinity of the consciousness; or, in the

consciousness of the infinite, the conscious subject has for his object the infinity of his own nature. (Feuerbach, 1841/1957, p. 2–3)

Surely, a perception of another (and another and another, ad infinitum) aspect or moment of the bright, pulsing infinity of consciousness (or its so-called

endless ‘‘emptiness’’) can thoroughly stun the so-awakening individual. If he is not stunned, perhaps he has not yet arrived close enough to absolute

consciousness to warrant terming his experience ‘‘an awakening to the absolute consciousness.’’ As Lord Krishna states to his awakening devotee, Arjuna, in

the Bhagavad-gita, 11.3–6 (translated by Mitchell, 2000, p. 122–26).

Look, Arjuna: thousands, millions of my divine forms, of every color and shape.

Look: the sun gods, the gods of fire, dawn, sky, wind, storm, wonder that no mortal has ever beheld!

Look, Arjuna! The whole universe, all things, animate or inanimate, are gathered here—look!—enfolded inside my infinite body.

But since you are not able to see me with mortal eyes, I will grant you divine sight. Look! Look! The depth of my power!

[11.21–24, Arjuna responds:] Your stupendous forms, your billions of eyes, limbs, bellies, mouths, dreadful fangs: seeing them the worlds tremble, and so

do I.

As you touch the sky, many-hued, gape-mouthed, your huge eyes blazing, my innards tremble, my breath stops, my bones turn to jelly.

Seeing your billion-fanged mouths blaze like the fires of doomsday, I faint, I stagger, I despair.

The Two ‘‘Margas’’ (‘‘Life-Paths’’) Toward Awakening in Indic Models

On the one hand, and in the context of Indic models of enlightenment upon which transpersonal psychology so much depends, transpersonalists are little

cognizant that nearly all of the ‘‘spiritual heroes’’ of its archive were primarily addressing practitioners of sannyasa marga

(nature-dwelling, ‘‘worldly’’ life renouncing couples, monks, and nuns, who spent many hours every day in meditative practice), or those who would become

sannyasins in their elder years, according to the Indic ashrama schema of ‘‘life stages.’’ The effect of decades of transpersonalists (unwittingly) using

sannyasin-specific scriptures and heroes to guide in-the-world Westerners of all ages is a matter worthy of further study. [vi]

On the other hand, transpersonalists are little cognizant of the grihasthya marga (sacred house-holder path) claim that substantial degrees of

awakening come to those who have achieved some twenty-five or thirty years of successful career (jati) and family life and the (awe-inducing)

births of grand- and then, (twenty-five years later) great-grand children. Thus, transpersonal therapists may be under-regarding (what deserves to be

termed) evidence of gradual awakening in their married clients’ lives, such as the challenges of creatively living up to marriage vows and family

responsibilities.

Here potential bypass issues regarding egoic relational maturity are to be addressed, as well as working through instances of surpass. While the term

‘‘working through’’ is conventionally applied to processing trauma or conflict (‘‘working through anger’’ or ‘‘grief’’), I have, in the first section of this

article, applied it to spiritual surpass events of increased capacities for love, courage, faith, forbearance, forgiveness, contrition, gratitude, and

other character-building ‘‘spiritual sentiments.’’ We might love each other more than we believe—granting credibility to such a possibility is an example

of spiritual surpass that can require much ‘‘working through’’ before it is deeply felt and embodied as true.

Bypass and surpass issues are thus, also, relative to the marga or ashrama (psychosocial stage of life: brahmacaryin virginal

youth, grihasthya sacred householder, vanaprasthya retiring grandparent, and sannyasin fully-retired greatgrandparent, stages that don’t apply to sannyasins who maintain lifelong brahmacarya, transmutational celibacy). For example, householders are guided to ethically increase their

financial success, while sannyasins lead simple, ascetic lives. In all cases, lifelong spiritual maturation is paradigmatic.

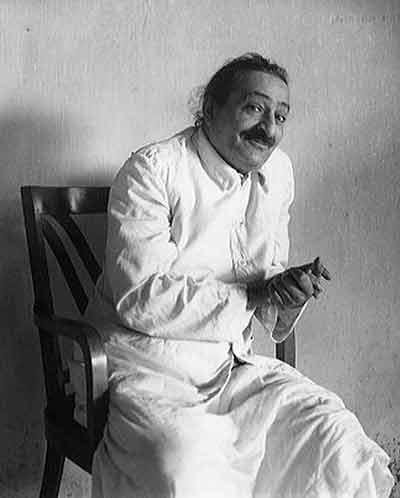

Meher Baba with Gustadji in 1922. Baba's favorite photo of himself.

Meher Baba and the Problematic of Spiritual Surpass

Who, if I cried, would hear me among the angelic Orders? And even then if one of them suddenly Pressed me against his heart, I should fade in the strength

of his Stronger existence, For Beauty’s nothing But beginning of Terror we’re still just able to bear. (Rilke, 1939/1963, p. 21)

On his unusually broad and complex scale of spiritually awakened states, Meher Baba distinguished masts (the ‘‘God-intoxicated’’ ‘‘Infinity-intoxicated’’)

from those who were more psychiatrically disturbed (by a more mundane aspect, one might say, of the Infinite manifestation). He, in fact, differentiated five

categories of problematic vairaghya (awakened detachment from less-mature concerns): God-merged, -intoxicated, -absorbed, -communed, -mad.

Yet, I will suggest that the ‘‘mad’’ group (those with undealt-with trauma, biochemical disorders, and bypass issues) too, can be usefully viewed as also

suffering with the grandeur of overwhelming spiritual truths perhaps hidden or tangled in mundane pathologies (i.e., hidden in the mundane ways of

describing their conditions, their struggles to have hope, to be forgiving and newly creative, etc.).

Overwhelming Awe and Dissociation/Depersonalization Disorder

Likewise, the DSM-IV-R distinguishes between self-induced, nonpathological meditative states and the pathological Dissociative/Depersonalization

Disorder.

Yet, the continuity between the former and latter is perhaps more noteworthy. For, the fact that ‘‘voluntarily induced experiences of depersonalization or

derealization [do indeed] form part of the meditative and trance practices that are prevalent in many religions and cultures’’ [my emphasis] ( DSM-IV-R, p. 488) is a matter well-worth pondering.

For, perhaps as these religions and cultures maintain, these ‘‘states’’ are the result of perceiving consciousness itself as awesome, miraculous, and

blissful. And, then, in such transfixed reverence when breathing suspends for minutes upon minutes and the pulse slows down, and the body becomes utterly

motionless or quakes profusely, perhaps the entranced one, the meditating one, is beholding a ‘‘reality’’ so profound, an ‘‘identity’’ so compelling, that

he has indeed become ‘‘de-realized’’ from the ordinary reality and ‘‘de-identified’’ from the ordinary identity to behold a more ‘‘convincingly real’’

reality as the Feuerbachian infinity of consciousness itself, of subjectivity itself.

The ‘‘Poised’’ Witness and Sequential Spiritual Surpass

How to endure such awe without being overwhelmed? As Meher Baba notes regarding the admixture of spiritual insight and problematic absorption, remaining

‘‘poised’’ is the crucial factor.

When a man in a particular plane, with his consciousness gradually involving [maturing], becomes completely dazed by the enchanting experiences of the

plane, the man is said to be a majzoob of this particular plane. Such a majzoob is completely absorbed and overpowered by the impressions

of the Illusion [partial knowledge] of the plane which consistently impregnates his consciousness. Such a man is commonly known as a ‘‘mast,’’ meaning

thereby that the man is ‘‘God-intoxicated.’’

On the other hand, if a man in a particular plane does not get absorbed in and overpowered by the fascinating experiences of the plane, but continues to

maintain his poise throughout while his involving consciousness is persistently impressed by the impressions of Illusion of that plane, he is then said to

be a salik of the particular plane. Such a salik, to all external appearances, behaves like a very normal man of the world even though

his consciousness is progressively involving and is completely dissociated from the gross world as far as his consciousness, fully focused on the plane, is

concerned....

There are, however, certain cases when a man in a particular plane is sometimes completely drowned in and absorbed by the fascination of the experiences of

the plane and behaves like a majzoob, and at other times he regains his poise and behaves like an ordinary, normal salik of the plane

(Baba, 1955/2001, pp. 136–37).

Oscillations in Spiritual Surpass and

Vyutthana

The DSM-IV-R has delineated its own form of the phenomenon of the majzoob-salik, albeit lacking a broad view inclusive of super-normative

states of consciousness, wherein meditators and those experiencing traumatic dissociation both describe their experiences as ‘‘unreal, unfamiliar,

strange...disturb[ed] in one’s sense of time’’ (DSM-IV-R, p. 488). The DSM-IV-R nosology further states that ‘‘depersonalization is a

common experience,’’ perhaps because one’s familiar ‘‘self-sense’’ is constantly being permeated with a flickering awe of new and unfamiliar inklings of the

Infinite.[vii] Meher Baba’s ‘‘poise,’’ however, points to the continuity of the witness, the Vedantic ‘‘ ka’’ or ‘‘who’’ of all subjectivity.

Is the innermost, real subjectivity best described as ‘‘impersonal,’’ ‘‘utterly personal,’’ or ‘‘transpersonal’’? Such debates run through the world

literature of mysticism and perhaps indicate the endlessness of spiritual surpass, where one sense of ‘‘ultimate’’ consciousness gives way to another and

another, even ‘‘more ultimate.’’ And perhaps, as the lore of the avatar maintains, at some indeterminate future time, such maturation will culminate in the

appearance of a fully-messianic world-uniting saint.

The verification of such an unsurpassable messiah is purely empirical. World-wide, enmity, injustice, and all manner of delusion would simply wither away in

Their presence. Indeed, according to the Bhagavad-gita, in the darkest times, the avatar or world-savior comes and awakens all beings to the

central enlightenment of the seventhousand year-old Sanatana Dharma (Eternal Ordering-way), ‘‘Vasudhaiva kutumbakam–The world is, indeed,

one family.’’

Depersonalization from a more limited self-sense followed by an evermore universal re-personalization, (over and over again) is known as vyutthana

, ‘‘re-arising from lesser to evermore matured states of consciousness.’’ Metaphorically described as ‘‘spiritual rebirth,’’ one is said pass through many

lives and deaths, thus vyutthana also refers to ‘‘resurrection’’ from deeply absorbed states wherein the distinction between living and dying is

approached. Such surpass encounters should be protected from regressive enframement, i.e., as being ‘‘birth traumas’’ (neonatal asphyxiation), particularly

where yogic breathlessness spontaneously occurs (kumbhaka, or during breath-suspending khecari mudra).

From a clinical perspective, what differentiates a ‘‘pathological decompensation’’ from a ‘‘salutary disorientation’’ is often a matter of how effective

the therapist’s words are in providing the majzoob-salik with helpful reorientation, with the ‘‘poise’’ to go forth (vyutthana) into more

inspired social involvement. In my twenty years as Director of the Kundalini Clinic for Counseling and Research (founded by Lee Sannella, MD, in

1976, the first ‘‘spiritual emergence’’ service in the US where the ‘‘spiritual emergence/emergency’’ population is akin to the majzoob-saliks), I

have found that clinical admiration as described above, can provide exactly such help (albeit with important qualifications, where periods of medication

and/or hospitalization deserve to be explored—at least at this point in the history of ‘‘talking cures’’).

Admiration Interventions with Surpass Issues

The spiritually-surpassing client is admired for coping with profound issues: the infinity of consciousness; the uncertain powers of interpersonal love or

of a happiness beyond desire or wealth; the elusive ‘‘mind-body problem’’ and the mystery of bodily aging/disease/dying and lineage (family) relationships;

the possibility of utter forgiveness or justice; ‘‘ineffability’’ and the limits of language, certainty, and binary logic; and the constant novelty and

sequential limitations of unfolding duration.

It is within such questions that clinical panic, terror, grandiosity, indecisiveness and impulsivity, depression, narcissism, borderline splitting, autism,

paranoia, etc., seem to gain an admirable, if also exceedingly fraught, integrity. How shall we evaluate the level of awakened skillfulness of the

therapist? Why not by her ability to foster creative love in evermore deeply disturbed persons, relationships, and families, as Meher Baba and other saints

inspire us to do.

If you value this knowledge please consider donating towards its production and dissemination worldwide in Sutra Journal. Be part of the effort to bring this knowledge to the world. Donations go towards the operating costs and promotion of the Journal.

If you value this knowledge please consider donating towards its production and dissemination worldwide in Sutra Journal. Be part of the effort to bring this knowledge to the world. Donations go towards the operating costs and promotion of the Journal.