Editor’s Note:

Pratapaditya Pal is an Indian scholar of Southeast Asian and Himalayan art and culture, specializing particularly in the history of art of India, Nepal and

Tibet. He has served as a curator of South Asian art at several prominent US museums including Boston's Museum of Fine Arts, the Los Angeles County Museum

of Art, and the Art Institute of Chicago, where he has organized more than 22 major exhibitions and helped build the museums' collection.

Published with permission from In Pursuit of the Past: Collecting Old Art in Modern India 1875–1950 by Pratapaditya Pal, Mumbai: The Marg Foundation, 2015.

On an evening like this, in the loneliness of this house,

in front of the river glittering in the moonlight,

in the ringing stillness where only sounds

from unknown peoples,

unknown dogs, unknown temples reach me,

where nothing overshadows the inner existence, one comes to oneself –

so it is said. –

Alice Boner[1]

About 250 kilometres upstream from Patna on the river Ganga lies the city of Banaras, one of the most ancient continuously occupied urban settlements on

the subcontinent. Not only is it the holiest pilgrimage site of the Hindus, but in one of its suburbs – Sarnath – Gautama Buddha preached his first sermon

sometime in the 5th century bce. Known as the Deer Park, the site was visited by the Maurya emperor Ashoka (304–232 bce); he raised a sandstone column

there whose capital is now the symbol of modern India, emblazoned on all forms of currency circulating in the country. Banaras is where all pious Hindus

aspire to be liberated from the chain of rebirth, which is why it is characterized as ‘avimukta kshetra’ or the land of final emancipation. Also called

Kashi, the city’s patron deity is Shiva as Vishvanath or Lord of the Universe whose temple, though not an ancient structure, remains the holiest Hindu

shrine, which most adherents of the faith strive to visit at least once in their lifetime.

The river-front view of Banaras, either from a boat on the Ganga or from the train, as one approaches the railway bridge from the east, is spectacular with

the ghats or banks of wide stairways rising from the waters to the impressive palaces of maharajas and rows of temple spires. Across from the ghats the

other bank is dominated by the fortress-like palace of the former maharaja of Banaras at the village of Ramgarh. Here one can see the hereditary royal

collections that include a fine array of local crafts for which the city has been well-known, especially its wide variety of metalwork. The city is also

famous for its textile industry, in particular for the silks and brocades which once were much in demand among the royalty and the rich. The luxurious

Banarasi brocade saris are still much sought after in northern India, especially among Bengalis, for bridal trousseaus. They are as indispensable and as

admired across the country as the famous Kashmiri shawls.

It was at one of the stone palaces that I arrived in early 1966 to join the staff of the newly founded American Academy of Benares.[2] The palace originally

was built by the Maharaja of Rewa, a former princely state in today’s Madhya Pradesh. Situated at Assi Ghat, the southernmost on the river, it is a

beautiful building, which was sensitively restored by local craftsmen testifying to the continued vitality of the traditional builders. (O.C. Gangoly wrote

effusively in his memoir of the deftness of the stonemasons and carvers of Banaras when he built his own house in Calcutta in the 1920s.) The Maharaja of

Rewa had left the palace to the Banaras Hindu University, after it was occupied for a few years by the scholar Alain Daniélou (1907–94) and by Raymond

Bernier (1912–68) the famous photographer of Indian architecture whose photographs were used by Stella Kramrisch for her Hindu Temple.[3] I worked at Rewa

Kothi, as it was known locally, for almost nine months and had the privilege and honour of meeting two of the four collectors of antiquities in the city

who will be discussed in this chapter. One of them was Rai Krishnadas who lived then in a professorial bungalow on the university campus, which was less

than 2 kilometres away; the other was Alice Boner who lived in an old house a few minutes’ walk from Rewa Kothi.

Alice Boner (1889–1981)

Figure AB.14 Photograph of Alice Boner with

the young Ravi Shankar in Zurich 1931,

about the time she first arrived in India.

© Museum Rietberg Zurich, Legacy Alice Boner.

Re-photographed by Rainer Wolfsberger.

I first heard of Alice Boner while a post-graduate student, as an eccentric European lady who lived in Banaras and was interested in the temples of Orissa.

We first met when I came to work in the city in 1966. She had published her seminal book on the Principles of Composition in Hindu Sculpture in 1962, which

I had read while in Cambridge and found fascinating. While I was in Banaras, her groundbreaking research with Oriya pandit Sadashiva Rath Sharma came out

as Śilpa Prakāśa and stirred up a controversy. I remember some scepticism about the authenticity of the original manuscript among certain art historians at

the time; if indeed it was a fake then hats off to the creator. It was also in Banaras that I realized that Alice Boner was a collector of old Indian art

and an artist herself.

The first thing that struck me about her was her height, especially in comparison with the petite Stella Kramrisch. The two must have seemed an odd pair

when they appeared together in 1940 at the Bharany shop, though Chhotelal does not remark on it. Alice was a few years older than Stella and was already a

septuagenarian when we met in Banaras. She was remarkably agile and active for her age and always gracious and generous. We were neighbours and she would

invite me to tea from time to time when she was not travelling. She had moved into what was “an old, half-dilapidated house on the holy river Ganges” (in

the words of her sister Georgette Boner) as far back as 1936, and never abandoned it until her departure from India over four decades later (figure

AB.15).[4]

Daughter of the Ganga

Figure AB.15 Photograph of the home of Alice

Boner,

Assi Sangam House, Banaras, 1974.

© Museum Rietberg Zurich, Legacy Alice Boner.

Re-photographed by Rainer Wolfsberger.

True, the approach through narrow gallis (lanes) was unprepossessing, but the house I visited was a testimony of Alice’s great aesthetic sensibility (she

was both a sculptor and a painter) and of her genuine love of the country and civilization. Her diaries are fascinating for her candour, her fervent

spirituality, the intensity of her feeling for India as well as her acceptance of the reality that was the country. She came to India late in her life; she

was already 45 in the twilight of the Raj but lived on for over three decades after Independence in that “half-dilapidated house” which continues to

flourish as a research institute for her adopted culture. Belonging to an affluent family, she used her wealth wisely like the good Swiss citizen she

was.[5] As a Hindu myself, I am not only amazed by her devotion to and admiration for India but for her love for the city of Banaras as is clear from her

diaries. Let us read her entry for February 27, 1936:

The stars arrange themselves and harmony prevails; peculiar determinations and relations. A soothsayer, who knows the happenings in India so well, said

that in thirteen days I will have a fortunate experience. In thirteen days I found this house on the Ganga.

This house is remarkably soothing and exciting at the same time. In it I feel I have returned to myself, to my home, my domicile. It is so intimate to

me, so inviting, so warm. It encloses me in love and opens the world to me. It unfolds the radiant earth in front of me, the most colourful life

surrounds me with the simple calm of a cloister. I feel fulfilled, happy, settled, borne, as if on a soft, flowing river.

[6]

She had many talents but as will be seen from the quotation above and other passages that will fill this section she was also a poet and a mystic. Almost a

year later on February 22, 1937 at Assi Sangam, she wrote the beautiful passage used as an epigraph to this chapter.

Romancing India

Alice Boner’s romance with India began as early as April 1926 when she watched a dance performance in Zurich. Among the performers was Uday Shankar

(1942–77), one of the first Indians to introduce the art-form to the West. (His younger sibling Ravi Shankar would expose the West to classical Indian

music in the ’60s.) Three years later in 1929, the year of the Great Crash, she met Uday Shankar again, this time in Paris, and she decided to collaborate

with the dancer, to visit India and return to Europe with a complete orchestra for live musical accompaniment. So in the following year she visited India

for the first time but their effort did not meet with success. Undeterred, they bought some instruments with funds provided by Alice and returned with

members of Shankar’s family among whom was the young Ravi. Though an aspiring painter at the time, he would ultimately excel with the sitar. Alice was the

mother hen of the group, making all arrangements for their material comfort as well as their rigorous training and professional arrangements (figure AB.14).

After five intense months the group performed in the Théâtre de Champs Elysée on March 3, 1931 and took Paris by storm.

Figure AB.16 Alice Boner with a figure of Devi,

Banaras, 1977. © Museum Rietberg Zurich,

Re-photographed by Rainer Wolfsberger.

Boner remained the major domo of the troupe until 1935 when she decided to return to her own vocation of sculpting and painting and to India, which had

continued to beckon her since her first visit five years before. She did not come to India to seek a career or to study its art, but to discover herself,

her inner reality; as she wrote in 1953, to develop from within. She was primarily an artist who declaimed, “Ambition is (for the artist) self

destructive,” and while struggling throughout her sojourn in India to express her creative energy, she interacted in a very personal way with the ancient

arts of the country with an intensity that no other collector discussed in this book experienced or perceived. In the process she also evolved almost

serendipitously into an insightful scholar whose relentless pursuit of the meaning of Indian architecture and sculpture has enriched our own understanding

of the visual arts of the Indic civilization.

In his comments about Boner, Chhotelal states, “Alice Boner… whom I met for the first time in 1940 with Stella [Kramrisch] shared the same love of Hinduism

and Indian art but was not quite as passionate.”[7] I however have a completely different impression from mining Boner’s diaries, as I will demonstrate

below. I think both were equally passionate but in different ways. Boner was more forthcoming in verbalizing her emotions in her diaries from which we

learn of her inner tensions and thoughts. Kramrisch on the other hand was a very private person, emotionally reticent, and in a sense remained an elusive

figure despite a longer life.

We can almost pinpoint the moment when Alice began collecting; the first entry in her diary mentioning an acquisition is for October 31, 1934. She had

arrived by boat from Europe in Colombo on the 27th and had then crossed the channel to Dhanushkodi in India, eager to begin work. That evening she wrote:

“I bought three masks and sent them to Calcutta. One is magnificent, the head of a hero with an alert face, wide open eyes and charming side burns; above

it a fantastic head dress.” The masks are now with her other collections in the Rietberg Museum, Zurich and clearly demonstrate her fascination with dance.

Though her principal interests were in Indian sculpture and portable paintings, as will become evident, she cast her net wide – though not as much as

Kramrisch, who I think was more compulsive.

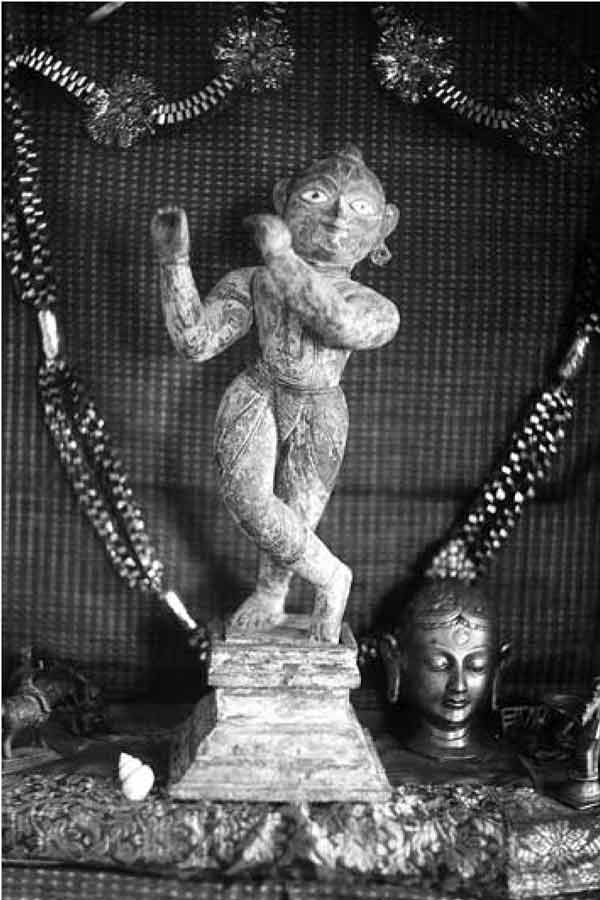

Figure AB.17 Photograph of a Ganesh sculpture

in Alice

Boner’s Banaras home.

© Museum Rietberg Zurich, Legacy Alice Boner.

Re-photographed by Rainer Wolfsberger.

That Alice particularly related to Indian sculpture and architecture is evident not only from her publications, but also from her diaries, which make

fascinating reading. In an entry for September 29, 1942, after narrating a particularly harrowing experience with security forces in the Kulu Valley (it

was wartime and she was a German-speaking foreigner) she was so upset that she wrote (upon returning to her home in Banaras):

How I bless the day when I left that place [Shimla] and returned to Banaras, and saw again some friendly faces and the majestic Ganga in front of my

house! As a reaction to the distressing experience, however, a singular calmness overcame me. I felt as never before free from fear of anything which

might happen to me, and also free from attachment to all possessions. I felt under these circumstances, that I would be able even to give away my stone

sculptures, from which I thought I would never part as long as I lived…

Thus, it is clear that she had already assembled a collection of sculpture by 1942 (figures AB.16, AB.17 and AB.19).

Her intense admiration for the stone sculpture of the country is also evident from a diary entry of January 31, 1954: “I would love to write a book, The

Stones of India, what they have meant to me and what they have meant for the revolution of India’s life throughout – what eloquent witnesses they are, what

messages they proclaim and how it is possible to love and understand a country through them!” Certainly I know of no more eloquent expression of the love

of Indian stone sculpture by an art historian or connoisseur, nor a more exciting prospectus for a book.

This ‘daughter of the Ganga’ from Switzerland, much as she adored Banaras, would transfer to the Himalaya (Almora being a favourite spot) to escape the

scorching heat of the summer. Once when she visited Kashmir in May 1953, seated in her houseboat “Melisande” she wrote:

My health and my spirits have until now been quite indifferent. I kept to myself, but was finally induced by Mrs. Ruegg to visit some dealers. While

looking for pictures and shawls my interest was suddenly awakened to a new subject by the last thing I intended buying – big copper vessels. I was

driven to it by an inner urge as soon as I saw the beauty bestowed upon them in these parts. Yesterday a selection was brought to me and when they

stood in my room they became irresistible. They are now on the mantelpiece, a tall royal Persian water jug, a Kashmiri water pot and a Ladaki

travelling pot. When I look at them they almost take my breath away. I have never known that a simple object could touch such deep springs of

sensibility. But they are no longer objects, they are living beings. They have a soul as well as a perfect body. They have a perfection blown out by

prana, each one in its own way. Their characters are very different, and yet they form a perfect trinity. The centre piece, the lordly water jug, can

stand alone without losing any of its majesty. The other two, more modest, cannot hold such an exalted position by themselves. They belong to the train

of the king and must stand on the sides, where they fulfil their appointed mission…. The Persian and Kashmiri vessels have dragon shaped handles, while

the Ladaki vessel has a straight handle, its shape too is not rounded but straight…. To say that they are perfect would not do them justice, they have

that impalpable quality which makes a work of art a thing of flesh and spirit…. They breathe the life-power of idols, and for the first time I

understand how the abstract forms of African idols can be felt instinctively or can possess divine power. There is something divine in such

realizations, worthy of worship. Here abstract art has reached its goal. How little do the moderns know about it! Abstraction per se will not do,

abstraction as the quintessence of a lifeprocess. Yes, here it is achieved without intellectual pretension, but oh, with what intellectual and

emotional experience!

Long as that passage is, I feel it is worth its weight in gold not only for demonstrating the serendipitous nature of a collector’s taste but also for

providing insights into an artist’s keen aesthetic sensitivity and poetic flight of fancy. It is also a subtle admonition to those who in their craving for

modernity often tend to ignore tradition. As one reads the passage even without knowing exactly what the objects were, one can almost envision them on her

mantelpiece as religious icons. As far as I know no collector has left such an evocative expression of his or her personal aesthetic interaction with

quotidian objects with such telling candour. It reminds me of the eminent American architect and designer couple Ray and Charles Eames’ discovery of and

romance with the simple pots of unfired clay on the heads of village women they encountered on their first visit to Nehru’s India as emblematic of the

harmony of perfect design and function.

Figure AB.18 Oil-painting of Samhara Kali by Alice Boner.

© Museum Rietberg Zurich. Legacy Alice Boner.

Photograph: Rainer Wolfsberger.

Being an artist, Boner’s mood changed often depending on the progress or frustrations with her own creative efforts. Indeed, the immense value of her

diaries is to share with her those wild mood swings, her moments of deep despair as well as others of exultation when (in her inimitable language) her

“cramped heart has widened and expanded”. After a break from “a few weeks of hard dogged labour on Kali [a painting she took a long time to complete]

bringing me to the brink of despair”, she returned refreshed and, almost in a state of beatitude, confided to her diary on March 7, 1954:

I see again! I feel again. Everything appears more beautiful tonight. The Jaipur picture of Shiva and Parvati on Kailash [which must have been before

her] has become a mighty, ardent poem of the icy heights of Shiva’s abode. The wriggling snake heads above the seated Vishnu on Sheshanaga form an

aureole of splendour never dreamt of before. My own Kali whom I left in dismay this morning has improved her looks [figure AB.18] during the day and

when just now I saw a few reproductions of Chagall, Miro, Bonnard, Matisse, which at another time would have given me an inferiority complex on account

of their boldness, just made me laugh on account of their poverty and their rawness.

In the Company of Miniatures

As I read Boner’s remarkable diaries to which she confided her innermost thoughts and feelings without any constraints (“In a diary one is one’s own

witness,” she wrote), I marvelled how with a few scratches of the pen she had expressed the essence of the Indian aesthetic experience that volumes of art

history by eminent historians had failed to do. Here is the entry for March 8, 1954:

In Indian miniatures I begin to see more and more the principles of composition based, if not on the strict division of the circles – as in the ancient

sculpture – then, on the consequent division of the rectangle, which results in definite directions in the space determining each picture. Even in the

Nandi pictures, which seem to come from an impulsive and almost naturalistic brush, the principles clearly underly them.

Figure AB.19 Krishna icon on the altar at Alice Boner’s home, Banaras. © Museum Rietberg,

Zurich, Legacy Alice Boner. Re-photographed by Rainer Wolfsberger.

Almost two years later (February 7, 1956), she wrote again about her perception of and interaction with the world of “miniature pictures” (as she referred

to them) after a meeting on February 3 with Swami Pratyagatmananda, the author of the book Yantram, a subject that played a fundamental role in her

understanding of the inner meaning of compositions of Indian sculpture, which resulted in one of her most significant books.[8] After remarking on how the

Swami’s book had helped her in understanding yantras and sculpture, she penned this remarkable passage about pictures:

In the Indian miniature, at its best, the essence of a world is concentrated on a surface not bigger than the palm of one’s hand; and if not a whole

world, then certainly of one definite aspect, with the inner meaning of its manifold manifestation. One small miniature will reveal more truth and

inner beauty, as time goes on. It is an inexhaustible fount of messages, unfolding one after another from the intimate thought imprisoned in it. It is

this which makes it so precious, much more than the exquisite workmanship, colour and gold. An Indian miniature is company, a modern abstract painting

is not. It does not look at you, does not speak to you and, after a while, dissolves itself into nothingness, no matter how well painted…. The subtle

essence of Indian miniatures has taken possession of me. They have also guided me in the new direction my work has taken.

I was elated as I read this passage for she had expressed more elegantly (and she herself was a part of the Western modern movement) what I had myself felt

about abstract paintings: that while intellectually fascinating for me they lacked that rasa that I would extract and taste often when looking at

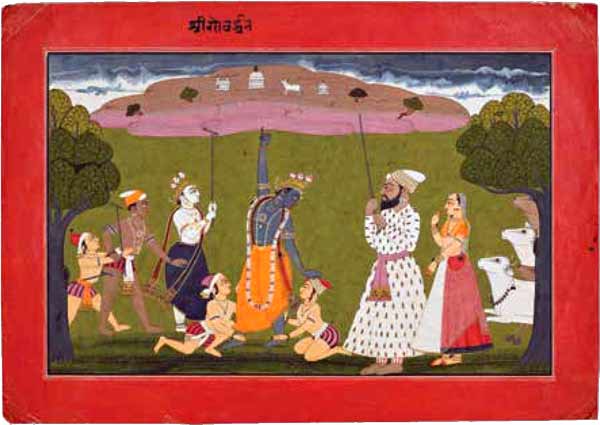

traditional painting of all cultures. I offer here, as a vindication of Alice’s eloquent passage about the charm of “miniature” pictures, a seemingly

“monumental” composition of Krishna (she had recorded with remarkable candour her recurrent conversations with him in her diary in an echo of the

16th-century Rajput princess Mirabai) holding up Mount Govardhan (figure 5.20).[9] In this beautiful picture by the Guler painter Manaku, a touch of humour

is introduced when the two boys kneel to provide support by anchoring the god’s feet firmly to the ground, even as Krishna effortlessly holds the hill on

his little finger. The Krishna image on the altar of her house is not a great work of art but it was her constant companion (figure 5.19).

The Search for her Innermost Consciousness

Boner lived roughly half of her long life in India, which she adopted as her “second home” (in the words of her sister Georgette) but unlike other

foreigners, she was fair in dividing her collection between her adopted home and the land of her birth. Her diaries make it clear that she loved India, but

she never ignored her roots. Nor did she forget her local museum, Bharat Kala Bhavan – which was only a mile or so away from her house on the Ganga at Assi

Ghat.

While her diaries remain her “own witness” to her spiritual and intellectual search for the meaning of her inner pilgrim’s progress in the city of

Vishvanath, and to her intense love for the baby Krishna, reminiscent of the Indian devotee or bhakta Mirabai, it is in C.L. Bharany’s memoir that we

encounter her Swiss thrift.[10] He narrates poignantly how in 1942 after the death of his father Radhakishen, who had also helped in enriching Boner’s

collection, he offered her an illustrated manuscript but she refused to pay his asking price. Remembering that his father never bargained, the son, still

grieving for his loss, was in a dilemma: should he succumb or not? In the end he decided not to sell, held on to the manuscript until 1950 and then broke

it up – which he regrets – and sold individual folios for a lot more money. Thus, Boner’s refusal ultimately provided the young dealer with the capital he

needed for starting his own business; this too would have pleased the Swiss lady.

Earlier once Bharany asked Alice when visiting her in Banaras why she had left her beautiful home in the Swiss mountains (in fact in Davos, which has today

become the home of the World Economic Forum where the rich meet ostensibly to solve global economic problems while relaxing by skiing) to live in “this

heat” in Banaras. Boner apparently responded with a silent, “peaceful” smile. I am sure, were she to have read the recollections of the octogenarian

Bharany in whom she saw “the same spirit of straightforward give and take [as in his father],” as she wrote in a testimonial to both in 1950, her reaction

probably would have been another “peaceful” smile.

Figure AB.20 Krishna Lifts Mount Govardhan with His Little

Finger,

illustration to a Bhagavatapurana series, by Manaku, Guler, c. 1750, 20.9 x 30.2 cm.

Formerly Alice

Boner Collection. Courtesy of Carlton Rochell Asian Art.

Like Woodroffe, Coomaraswamy and Kramrisch, Alice Boner too could be considered as having had an

Indian soul in a foreign body. I have already alluded to her visit together with Kramrisch to Bharany in Calcutta but there is another heartfelt entry in

her diary about a visit with Stella on January 20, 1940 in yet another mood of despair:

As a last resort [she writes] I fled to Calcutta, in order to breathe another air. Stella Kramrisch took me in and I slowly came back to myself. I had

human contact, and I saw Stella in her intensive work, her untiring dedication to the goal of her life, her courageous attitude. I felt ashamed. I had

no right to give in to a desperate mood…. My soul returned to me.

She did not mention Coomaraswamy in her diaries, but she did quote a short passage about the goddess Kali from one of Woodroffe’s books, which is not

surprising for both shared a passion for the goddess. It would be appropriate to end this brief discourse on this European scholar/collector with yet

another passage from the “witness” of her inner thoughts penned at her beloved Banaras on January 26, 1953 (India’s Republic Day):

The Indian landscape in its primal breadth and virginity is like strong wine to me…. I was as if elevated from the mesh of the world, and earth and sky

were my home…. I fell here in cast nature, in the real home, in the home of the harmless. I see the doors opening when one surrenders and submits

oneself to the grace of God, and goes out with the cast world.

I hear echoes in the passage of Rabindranath Tagore’s song where he beholds “the sky filled with the sun and the stars and the world...filled with

life”, and “in wonder” his songs gush from his heart.

On January 24, 1940 Alice visited Santiniketan and “was received most kindly by Tagore”.[11] They did not talk much but she did convey Kramrisch’s message

that the poet send one of his Bengali manuscripts to the British Library. Boner was in Ajanta when she heard the news of Tagore’s death and in her diary on

August 8, 1941 she ended her private tribute by declaiming: “And for his country I believe that he represented its innermost consciousness and that he was

the highest expressor of her Dharma.”

It was also Alice’s objective in her wonderland to discover both her adoptive country’s and her own “innermost” consciousness. It would have been

appropriate if this “daughter of the Ganga” had died at Assi Sangam, but for health reasons she returned to her homeland in 1978 and passed away in Zurich

on April 13, 1981. Part of her ashes, however, were brought to India and consigned to her favourite river by her close collaborator – the brahman pandit

Sadashiva Rath Sharma.

[1]

Boner et al. 1993, p. 236.

[2]

Later the name was changed to American Institute of Indian Studies and it moved to Gurgaon near Delhi.

[3]

There was some misunderstanding between Stella and Bernier about the use of the photographs and I heard that the annoyed Bernier had bought up all

available copies of the original edition of the book and lit a bonfire. Subsequently the book, regarded as a classic work on temple architecture, was

reprinted.

[4]

Boner et al. 1993, p. 7. See also Boner and Fischer 1982.

[5]

Kuratli and Beltz 2014 for the biographical information about Alice Boner.

[6]

For this and all following quotes and references to Alice’s diaries see Boner et al.

1993, pp. 93, 106, 158, 175−76, 187, 201, 225, 236, 273, 285.

[7]

Bharany 2014, pp. 51–52.

[8]

According to Debashish Banerji who kindly read a first draft of this manuscript, “Swami Pratyagatmananda Saraswati was the sanyas name taken by

Pramathanath Mukhopadhyay, another Tantric friend of Sir John Woodroffe [see chapter 2] and a teacher of mathematics at the National College Calcutta (now

Jadavpur University), whom the latter has featured in some of his books on photographs demonstrating yoga postures.” I should add that in her diary entry

of her visit with the Swami, Alice informed him that she had also met Pandit Gopinath Kaviraj, a most eminent Indian scholar and philosopher of Banaras who

gave her a lot of encouragement in her work and who had also assured her that she was on the right path in seeking a connection between temples and

yantras.

[9]

This painting once belonging to Alice Boner recently came to the art market from a private Swiss collection. I wonder if it was consigned by a member of

the family, as unlike many collectors in this book Boner never sold a work of art from her collection. See Kathleen Kalista, Carlton Rochell Asian Art

(exhibition catalogue), New York, 2015, pp. 58–61, #20. I am indebted to Carlton Rochell for the image; also see Boner et al. 1994.

[10]

Bharany 2014, pp. 51–53.

[11]

It is surprising that Stella did not accompany Alice to Santiniketan and the latter says

nothing about Tagore’s response to the request.