Author's Note: This is a three part article giving insight into the traditional six Vedic seasons. In a previous article about the zodiac, I compared seasonal and stellar correspondences. This section aims to give a felt-connection to the emotional nature of the seasons.

Rtu Chakra Wheel of the Seasons by Freedom Cole

Seasons as Vibhāva

The season themselves can trigger emotions within us.[1] Indian culture has a complex

science of emotion from great antiquity.[2] Emotional experience is a complex process

of multiple factors: triggers (vibhāva), affects (bhāva), feelings (ālambana), and emotions (rasa).

[3]

In this context, bhāva correlates to the scientific term affect. An affect is a biological pattern that triggers emotion and

directs attention in a specific way.[4] For example, the affect of fear is experienced

as the speeding up of the pulse and respiration; the face becomes cold, pale, sweaty, and immobile; there is a gripping sensation in the chest; and the

hairs stand.[5] That biological response is the affect of fear.

A feeling is the awareness of an affect. This awareness becomes an emotion (rasa). An emotion is the subjective experience of an

affect, or what is called the affect through the lens of our perception. An affect and a feeling may last only a few seconds, but an emotion will last as

long as the memory lasts.

There is a trigger (vibhāva), or a condition that excites the affect. This vibhāva is the cause (kāraṇa) of the affect (bhāva). It is composed of the excitant (uddīpana: that which inflames); and the supportive perception (ālambana[6]). The trigger (vibhāva) can be a

perception, a memory, an inner drive, a cognition; and according to Vaidik and Tāntrik perspectives, the season can also act as a trigger. The seasons

triggers us to feel a certain way, which evokes certain emotions and moods. (A mood is a persistent state of emotion that remains for hours or days.) Even

the imagery of a season can evoke a particular mode, or make us feel something more deeply.

In the Sanskrit poetry (kāvya) literature, nature and the seasons are described in vivid depth with the intention of evoking an emotional

response.[7] Imagery about the weather and its associated colors, temperature, and

activities is utilized in stories to deepen the emotional expression and to bring emotional life to the story. In the Rāmāyana, Rāma cries in

sorrow during the Rainy Season as he is missing his kidnapped wife; and the longing and despair are deepened through the imagery of the rain. Poetry about

the seasons needs no other reason in Sanskrit literature than to describe the seasons with beautiful language. [8]

Grisma Devi

In the Summer season (grīṣma), people wear white to deal with the heat. Woman smear themselves with sandalwood paste, spray themselves with water,

and wear flowers that cool them.[9] Thin, wet, white clothing is an erotic poet’s

dream. Summer is the season of jasmine, and everyone enjoys the cooling moonlight, which excites the passion. [10] During the day, the heat is so unbearable. Even the shade hides under the feet

of the trees seeking shade when the summer Sun is on the meridian.[11] People sleep

during the noontime. Everyone is bathing in the waters – even people who you don’t normally see. One is advised to take fruits to counter the heat

exhaustion, and to make love late in the night when it is cooler.[12] Āyurveda

recommends increasing salt intake to increase water retention in the body when it is hot and dry. Wine is not taken, or in very limited amounts, in the

Summer (and enjoyed in the Winter months). Sugar-sweetened buffalo milk cooled by the stars and moonlight is the magic drink. [13]

In the Rainy Season (varṣa), the skies are filled with clouds, and the rains make the ground muddy. In the Maṇḍūkī Sūkta of the Ṛgveda, the frogs celebrate the return of the rains after the hot Summer. It is said they are like Brahmins who observe the seasons portioned from

the twelve parts of the year, as ordained by the gods (devahita).[14] The

frogs start to croak, just like the Vedic students who have started school and are repeating after their teachers. [15] The mountains are said to appear to be doing Vedic recitation (as so many

students are practicing during this time).[16] Peacocks love the rainy season and

dance, while umbrella-like mushrooms show up like encampments of a royal army.[17]

The religious texts describe the dark clouds that cover the brilliance of the Sun as being similar to the external forms of God (Saguṇa Brahman). [18] The poetry literature describes a swelling cloud, which is partly light and dark

at points, as resembling the darkening nipple of a pregnant woman.[19] The religious

texts describe the overflowing gullies and unrestricted rivers as a person with uncontrolled senses after having come into prosperity. [20] The rivers are filled and rush towards the ocean like the senses of pseudo-yogis

whose hearts are filled with desires rushing towards their desired objects.[21] The

turbidity of the rivers swelled by the rain is the disturbance of the mind by love and passion. The poets liken the swollen rivers with impure waters,

pulling down trees and breaking swales, to an unchaste woman.[22] Bhartṛhari says

that even bad rainy days become good days in the embrace of one’s lover.[23]

Sharad Devi

In Autumn (śarad), the water loses the turbidity it had in the rainy season, just as fallen Yogis are purified by resorting to Yogic practice

again.[24] The Ṛṣi Parāśara has very spiritual expressions of the seasons, and says

that the sky is clear of clouds like the heart of the ascetic whose cares have been consumed by the fire of devotion. [25] And the receding of the water from the banks of the rivers is like the wise, who

by degrees shrink from the selfish attachment to wives and children.[26] The poets

look at the calming rivers and see the tiny ripples on the water as the play of the brows of artful women. [27]

In the fields, the grains are bending due to their ripeness, and the āmalaki fruit is ripening to blackness. Platforms are built in the fields to protect

the ripening grains from boars.[28] Autumn is compared to a young woman

in the bloom of her youth,[29] as the fields are ripe with crops ready to nourish and

make men wealthy. The season is seen as joyful, bountiful and playful. The earth is beautiful from the previous rains. The flowers of the forest tree and

the abundant bee-laden lotuses are like eyes eagerly appreciating each other’s beauty. [30]

In the Winter season (hemanta), one can no longer sleep in the open through the nights, which are cold and long.[31] There is no difference felt between liking the Moon or the Sun. [32]

People go inside their homes and the focus is on entertaining, drinking, eating and relaxing. The monkeys are shivering, the cattle languish, the dog gets

into the kitchen and won’t leave, and men draw their arms inside their shirts.[33]

There is a silence from the animals outside, and the snakes move slowly, while the jujube fruits ripen. [34] The poets reference the low, southerly Sun as going in the direction ruled by

Fire (Agni) during the winter, as if afflicted by the snow.[35] Even in southern

India where there is no snow, they still use the imagery of snow to create the mood of the Winter season. The poets say that being inside on the Winter

nights while snow is on the house makes lovers embrace each other tightly.[36] The

poets see the long nights as good for amorous activity, and the intimacy brings more heat than the blankets. [37] Even the Āyurvedic texts talk of driving away the cold by the embrace of

beautiful women with well-developed thighs, breasts, and buttocks.[38] Most important

is staying inside where it is nice and warm.

In the Cool Season (śiśira), the cattle of the village and the wild animals become thin and shaggy. [39] It is called the Season of Blankets, as people pile them on to stay warm. The

first part of Winter was fun, as the harvest was finished and there was joyous sharing; but the Cold continues on and becomes dreary. They advise taking

bone-broth soup to stay healthy.[40] Women smear their breasts, buttocks and roots of

the arms and thighs with saffron tea.[41] It is a slow-moving time with the gradual

ripening of the white mustard plants.[42]

The end of Cool Season is the time for agriculturalists (and particularly permaculturalists [43]) to do earthworks. There is nothing growing in the fields and it is cool enough

to do hard work outside. Tree-planting does not happen till the Rainy Season, but if one waits till the hot season to do earthworks, the ground will be too

hard to dig.

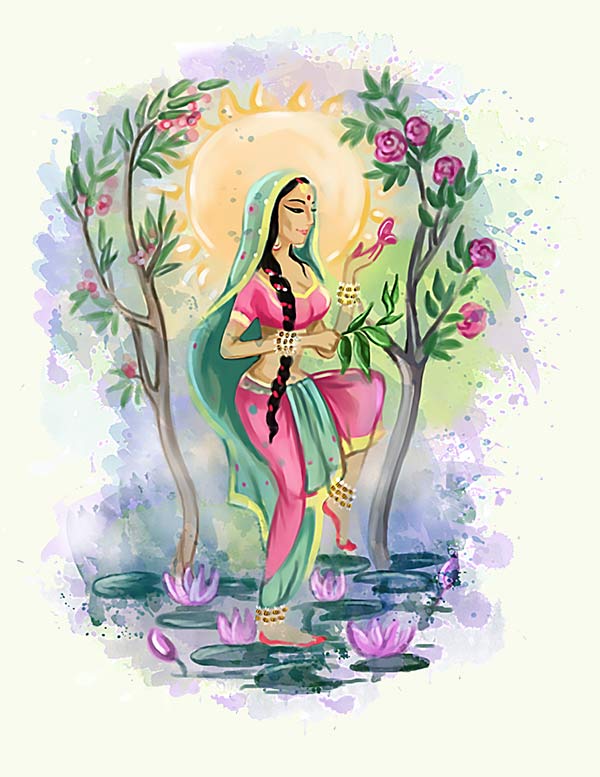

Vasanta Devi

The Spring season (vasanta), is personified as a goddess stepping into the barrenness, with sprouts issuing forth from her presence. The fresh

onset of Spring is compared to a newly married bride[44], excited to be with her new

husband and bringing joy into a new home. Spring can also be personified as a god of love – the best friend of Kāma (Cupid), and determined to pierce our

hearts. Spring makes the arrows for Kāma’s bow with flowers. When everything is blooming, Kāma can strike anywhere. [45] Girls are wearing crowns made of flowers, and children are invigorated and

playing.

All the animals of nature feel the love and passion of this time. The crane is constantly making love to his mate; the parrots are together in the trees;

the lions cuddle; the wolves are gleaming in their cave; the rhinoceros are licking each other pleasurably; and monkeys, cats, rabbits, elephants, buffalo

and deer are all described in their fondness of their mates.[46] “Who would not

become lovesick in the Spring when the atmosphere is all around charged with the fragrance of tender mango leaves and flowers, and the bees are intoxicated

with sweet honey?”[47]