photo by Vikram Zutshi

Dr. Long is Professor of Religion and Asian Studies at Elizabethtown College, in Pennsylvania, USA. He is associated with the Vedanta Society, DĀNAM (the Dharma Academy of North America). A major theme of his work is religious pluralism. Dr. Long has authored three books, A Vision for Hinduism: Beyond Hindu Nationalism, Jainism: An Introduction, and The Historical Dictionary of Hinduism. In this candid conversation with Vikram Zutshi, Dr.Long talks about his early fascination for Hinduism, the difference between Dharma and Religion, Hindutva, religious conversion and the Academy.

Sutra Journal:

To what do you attribute your initial foray into Hinduism? How did it evolve into a lifelong identity?

Jeffery D. Long:

My journey to Hindu Dharma began in my childhood. As I have described elsewhere ( http://www.sutrajournal.com/in-appreciation-of-the-gita-jeffery-long),

my father was in a terrible accident when I was ten years old. When I was twelve, he took his own life. This sparked an intensive quest for answers. What

happens after we die? What is the purpose of life, with all its suffering? I found many answers in the Catholic tradition in which I was raised, but not

all these answers satisfied me. The idea that we are reborn to learn life lessons and evolve toward a state of spiritual perfection made intuitive sense to

me before I knew anything about the Dharma traditions that teach this. Hindu Dharma in particular first came to my attention through western popular

culture. In my case it was the Beatles – mainly George Harrison – and the movie Gandhi that grabbed my attention. I have always been interested in

science, especially astronomy, so Fritjof Capra’s book The Tao of Physics (recently discussed in Sutra Journal

http://www.sutrajournal.com/fritjof-capra-and-the-dharmic-worldview-aravindan-neelakandan

) was a major influence on me. Harrison, Gandhi, and Capra pointed me to the Bhagavad Gita. Finding this wonderful book at a sale in a church

parking lot was a major turning point in my life, at which point I was fourteen years old.

I am really not a person who falls for passing fads. When I became interested in Hindu Dharma, it was a deep and all-consuming interest from the beginning.

The question for me would be when did begin to identify with Hindu Dharma? For a long time, I still saw myself as a Christian, though an unconventional and

independent-minded one, bringing beliefs into my worldview from other traditions – not only Hindu ideas, but from other traditions as well – seeking truth

in a pluralistic fashion, and drawing from many sources.

The next turning point for me was in college, at the University of Notre Dame. Notre Dame is not only a Catholic university. It is a very, very Catholic

university. It did not take long for me to see that I was moving in a direction that was incompatible with being a Catholic, at least the kind I had

intended to be. I was interested in the priesthood and in being a theologian, pursuing a career of spiritual and intellectual exploration. But the church

was not open (with the exception of certain individuals) to the kind of exploration I wanted to pursue. I gradually stopped seeing myself as Catholic, or

even Christian at all (since my disagreements were not with the Catholic Church per se, but with Christianity as a whole). I began practicing Siddha Yoga

with the guidance of a teacher who became a spiritual and an intellectual mentor to me. Even though not all practitioners of Siddha Yoga call themselves

Hindu, a Hindu worldview and practice are clearly involved. I felt liberated. I had finally found a group of practitioners, and a practice and worldview

that I could embrace fully, without the sense of disjuncture that I had long felt in the church. I began to identify myself as Hindu, but I was not really

sure if this was a proper thing to do, given that most people saw Hinduism as something into which one needed to be born.

The next step came in graduate school, when I met my wife, who is Indian and Hindu by birth. When we married in India, now more than twenty years ago, I

had the opportunity to formally affiliate myself to the Hindu tradition through a ceremony performed by the Arya Samaj. After we returned to America, and

especially after settling in Pennsylvania, in our teaching jobs, we became more involved with the Hindu community. I have been accepted warmly and without

reservation. The fact that I was not born into the tradition is not seen as preventing me at all from participating in it.

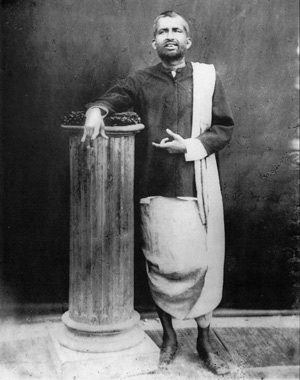

About ten years ago, we felt drawn to the tradition of Sri Ramakrishna, and took diksha, or initiation, with a swami of the Ramakrishna Order, who is our

guru in that tradition. It is with this sampradaya that I identify the most, due to many factors, including spiritual experiences I have had in it. We are

very close to our guru, and feel that here we have found our true, spiritual home.

Sutra Journal:

What are the tenets of Hinduism that make it stand out from other religions and what are the commonalities?

Jeffery D. Long:

An entire series of books could be written about this question! There are certain tenets of Hinduism that it shares with other Dharma traditions, like

Jainism and Buddhism: ideas such as karma and rebirth, and the goal of moksha, or liberation, from the cycle of rebirth. These traditions also affirm

certain basic moral values, as found in the yamas of the Yoga Sutra, the vratas of Jainism, and the pañca-śīla (or five

precepts) of Buddhism: nonviolence, truth-telling, non-stealing, self-control, and non-attachment (though the fifth of these, in Buddhism, is not taking

intoxicants). Hinduism stands out from the other Dharma traditions in its affirmation of the authority of the Vedas, the ancient record of the

direct perceptions of the rishis, or sages, into the true nature of reality. There is also a strong affirmation in Hinduism of the validity of

many paths to truth: ekam sat bahudha vipra vadanti.

Dharma, as many will point out, is not the same as religion. It includes the elements that are generally placed in the category of religion, but it

encompasses a good deal more. If we wanted to place the religious aspects of Dharma in a framework that would include all the world religions and ask,

“What are the commonalities?” I think we could say that all religions are rooted in an aspiration to perceive and experience truth at a greater level of

depth than is available through the senses alone. They are based on a deep need for a meaningful narrative into which we can place our lives and see our

many sufferings not as random events, but as purposeful, and as leading to a higher, transcendent aim. (See

https://www.academia.edu/13423132/The_Need_for_a_Meaningful_Narrative_Prabuddha_Bharata_January_2015

).

In Sanatana Dharma, or Hindu Dharma, and the Dharma traditions generally, we find a completely different conceptual universe from that presupposed, for

the most part, in the Abrahamic religions.

I am speaking now, of course, at a very high level of generality. It is important not to oversimplify when speaking about people’s deeply held worldviews.

It is certainly true that there are many individuals who practice Abrahamic religions but have beliefs similar to those of the Dharma traditions. But if we

look at the mainstream, or at generalities, as could be found in a world religions textbook, Abrahamic traditions tend to teach that the world was created

at a particular time by one supreme deity. This deity is also the moral judge of humanity. Just as the universe began at a particular time, it will also be

brought to an end, at which point there will be a judgment. The souls of the good will experience an eternal reward, and the souls of those who have

strayed from the divine will are damned forever. The supreme deity intervenes in history, and each of the Abrahamic traditions has its own variant on the

same basic story of God entering into covenants with human beings, sending prophets to make the divine will known, and so on. And of course there is also a

felt need to convert others to these traditions, especially since we each have only one lifetime in which to get right with God.

The biggest exception to everything I have just said is the original Abrahamic tradition, Judaism, which is traditionally a non-proselytizing tradition

(although the term proselyte originally refers to a person who converts to Judaism). There are some Jews who believe in rebirth, and most Jews do

not believe in eternal damnation. In the Christian and Islamic traditions, these are mainstream ideas. But again, it is always possible to find a great

many exceptions.

I do not think that Hinduism, or any religion for that matter, is just like any other religion. Each religion is unique. Each has its own worldviews, its

own internal dynamics, and its own distinctive practices.

If the question is what makes Hinduism stand out more than most, I would have to say the internal variety that the basic Hindu worldview accommodates.

It is controversial to say that Hinduism is diverse, if by this one means that it lacks unity or cohesion. It does have unity. But it also allows for

incredible diversity, and respects the freedom of each person to find his or her own way to truth

.

Sutra Journal:

Please elaborate on the notion of 'Self' and 'Consciousness' in Hinduism. What are the differences with the Jain and Buddhist view? How do these differ

from western philosophy and/or the Freudian model? Do they ever converge (perhaps in Carl Jung/Henri Bergson)?

Jeffery D. Long:

There are many views on this topic in Hinduism. (See

http://www.sutrajournal.com/sad-darsanas-six-views-on-reality-jeffery-long

). Vedanta, the Hindu tradition I practice, sees consciousness as basic to the nature of reality. The nature of reality is anantaram sad-chid-anandam, or infinite being, consciousness, and bliss. This is what the Upanishads call Brahman, which is also

affirmed to be identical to Atman, or our fundamental Self (and in contrast with what we conventionally call self, or ego). Materiality, in this

view, is a projection of consciousness. This is the view of Advaita Vedanta, as I understand it.

The Buddhist conception is very similar to this, except the Buddhist tradition shuns the term Self, as containing a residue of grasping, or

egotism. In both traditions, one seeks to disengage from the ego and identify with consciousness as such: pure awareness, with no “I, Me, Mine” – if I may

quote George Harrison. This absorption in pure awareness – that is, nirvana – is what brings about moksha, or liberation from the cycle of

rebirth.

The Jain conception is different from these two to the extent that the Jain tradition does not take materiality to be a projection of consciousness, but an

independent and distinct type of entity. The ultimate aim of Jainism is to disentangle the conscious, living being – the jiva – from inanimate

matter or energy, which takes the form of karma. But all three of these traditions are aimed at the liberation of the practitioner from the cycle of karma

and rebirth.

Western philosophy – again, with important exceptions – has tended to see consciousness as distinct from matter. Consciousness is either infused in matter

by God (a biblical view), or it evolves from matter through natural processes (a secular view, based on a materialist philosophy). In Western thought, the

view that matter is a projection of consciousness is called idealism. It is not unknown, but it is a minority view – though gaining traction as

the implications of quantum theory become better known and understood.

Freud, as far as I understand, was committed to a materialist worldview. Consciousness, in this view, evolves from matter and is determined by material

processes: the chemistry of the brain, and of course various traumas experienced in our lifetimes, especially in the early stages of childhood. But it is

also possible, on a Freudian view – indeed, this is its whole purpose – to transform our consciousness through therapeutic practice, primarily the practice

of talking through one’s fears and anxieties. Such a therapeutic approach can be seen, I think, as approaching the Dharmic one, which would be further

supplemented by practices like meditation. But the Dharmic approach can deal with certain things that therapy might bring up – such as a past life memory –

straightforwardly, while materialistic paradigms would be puzzled by such phenomena.

The other thinkers you have mentioned, Carl Jung and Henri Bergson – to whom I would add William James and Alfred North Whitehead – perceived early on the

limitations of the materialist approach, and often sought guidance from Dharmic perspectives, or in some cases, replicated Dharmic perspectives. The degree

to which each of these thinkers was able to free himself from the materialist paradigm varies, and could of course be debated. And it should also be noted

that, while the materialist paradigm has its limitations from a Dharmic perspective, it is not without value. The degree to which physical health and the

condition of the brain shapes our consciousness from moment to moment is difficult to overstate – although one could argue that materialism essentially

consists of just such an overstatement. Recent dialogues between the Dalai Lama and neuroscientists, to cite just one example, have great potential; for

science could conceivably aid practitioners in the Dharma traditions in cultivating practices with maximal benefits on the neurochemical side, while the

Dharma traditions can of course illuminate both physical practice and the wider metaphysical context in which spirituality occurs, to which at least most

forms of materialism do not allow access.

Sutra Journal:

What are your views on the reports of sectarianism and intolerance in India, as reported by the media in recent weeks?

Jeffery D. Long:

I think it is best if we take a global perspective on these issues.

Extremism is not unique to India, and is foreign to the true nature of Hindu Dharma, which has attracted people like myself because of its ethos of

openness, freedom, and, to quote Swami Vivekananda, “universal acceptance”

.

This does not mean, ‘anything goes’ in Hinduism. But Hindus have historically welcomed people from all religions in India. Persecuted communities such as

Jews, Christians, and Zoroastrians have all found a home in India. When I lived in India, I had friends from Sudan and Iran who had fled to India to escape

oppression. But extremism has arisen everywhere in the world in recent decades, and India, sadly, is no exception.

My field is not politics, but from what I understand, extremism tends to arise not, as one might expect, in conditions of extreme poverty, but when

conditions begin to improve and fail to keep pace with expectations. When people find their aspirations are not met, they become frustrated. The next step

is to search for someone to blame: usually another community. This unfortunate human samskara can be found everywhere, not only India, and certainly not

only among Hindus. This is a very fragile time for India, though, for as the economy grows, expectations will also grow. And if these expectations are not

met, violence becomes more likely to erupt.

Sutra Journal:

A segment of Hindus reflexively point to Islamist and western depredations whenever a negative report is published or label it a 'media conspiracy'. How

does one go about tackling this persecution complex without further polarizing the country?

Jeffery D. Long:

This is a difficult topic. There is a saying, “Just because you’re paranoid doesn’t mean they’re not out to get you”. There are, indeed, people and

movements that are avowedly anti-Hindu. The depredations to which many Hindus point whenever there is news about Hindus behaving badly are often real. One

cannot, therefore, simply dismiss this kind of reaction as completely unfounded.

At the same time, though, no one is justified in harming another or calling for the harm of others, solely on the basis of religious affiliation. Saying,

“The other group did it too” or “The other group does it more” is no justification for an atrocity.

Atrocity is atrocity, no matter who the perpetrator or the victims happen to be.

Swami Vivekananda said in his first address at the Parliament of the World’s Religions on September 11, 1893:

“Sectarianism, bigotry, and its horrible descendant, fanaticism, have long possessed this beautiful earth. They have filled the earth with violence,

drenched it often and often with human blood, destroyed civilization and sent whole nations to despair. Had it not been for these horrible demons,

human society would be far more advanced than it is now.”

These, I believe, are our true enemies: sectarianism, bigotry, and fanaticism. They infect all communities, and they need to be overcome.

Sutra Journal:

Do you see a softening of the religious divide caused by historical fault lines in India? What are some legitimate grievances Hindus may have against other

communities and how should the government tackle it?

Jeffery D. Long:

I see the biggest Hindu grievance against other religious communities as being in the area of conversion. This has been a major problem for a long time.

There are Abrahamic traditions – I am thinking of Christianity especially – in which seeking to convert others is a central mandate. This mandate has been

a major motivation – or at least a justification – behind imperialism and the genocides (both literal and cultural) that have accompanied it.

In the west today, especially in light of reflection on Christianity’s major role in massive historical violence, many Christians, especially liberal

Christians, have started to recoil from religious absolutism, and to question the way that the missionary mandate has been interpreted through the

centuries. I recently participated in a conference reflecting on the legacy of Nostra Aetate, a document of the Second Vatican Council, issued

fifty years ago, that revolutionized the way Catholics look at other religious traditions, encouraging dialogue and an emphasis on common values. At the

same time, the actual legacy of this document has been decidedly mixed. In offering a Hindu response at the conference, I pointed out Pope John Paul II’s

1999 call in Delhi for the evangelization of India, and the document Dominus Iesus, authored by Josef Ratzinger, the former Pope Benedict XVI,

which rejected the idea that other religions are equal dialogue partners with Christianity. If your dialogue partner wants to convert you, that, I believe,

is not real dialogue. Again, many Christians today would agree with me, and with the indignation of Hindus when Christian missionaries attack Hinduism.

Those Christians who have not yet awakened to the destructive nature of missionary activity are sometimes quite aggressive.

Now, I do not want someone in India to read this interview and decide he needs to hate and be suspicious of his Christian neighbor.

Instead of government intervention, I would like to see Hindus become more educated about Hindu traditions. Then, if a missionary wants to try to

convert them, they can respond intelligently to the missionary’s claims.

Another source of grievance that many Hindus feel is that the model of secularism that is practiced in India, which is designed to preserve the rights of

religious minorities, is seen to have been practically turned against Hindus and Hinduism. As with so many things in this interview, it is easy for me to

say as an American, but it seems to me the government of India should not be in the religion business at all. No one should be attacked, for any reason,

and the law ought to protect all people from physical assault or harassment, in the name of religion or on any other basis. And that is the extent to which

the law should go.

It is certainly beyond my expertise, but I wonder if India should adopt or experiment with something like the First Amendment of the US constitution:

freedom of religion, and no government intervention in religious affairs. I am really sticking my neck out in saying this. I am no legal or constitutional

scholar. But I feel that the US has done a better job of accommodating and assimilating minority religions and also protecting the freedom of the majority

by staying out of religion than India – modern India – has in trying to support it selectively.

And India does not need to look to the US, necessarily, for such a model. It is already in the ancient Indic ethos that permitted religious communities to

exist in relative peace and harmony in India for most of world history. This needs to be recovered and adapted to the modern world.

Sutra Journal|:

Many claim that there is a real anti-Hindu bias in the South Asian Studies departments of American universities and that Hinduism is often conflated with

Hindutva. How real is this claim?

Sri Ramakrishna Paramahamsa

Jeffery D. Long:

Rather like maya in the teaching of Shankara, it is both real and unreal. The American academy of South Asian Studies and of religion in South Asia is not

a monolith. It is extremely diverse. It is not uncommon for scholars to pursue this field of study because, like me, their lives have been transformed in

positive ways by these traditions. At the same time, there are also people who study religion because they have a political axe to grind. Some anti-Hindu

bias is really a general bias against any religious affiliation. The materialist paradigm is strong in the academy, so many scholars see all belief in

other worldviews as non-rational, superstitious, and retrograde, holding back social progress.

Then, there is simply what I would call tone-deafness or cluelessness about what it means for an adherent of a tradition to hold certain beliefs, texts,

practices, and persons sacred. It is often the case that people who study religion are part of a counterculture in the west that sees religion as

inherently oppressive. Such scholars project or assume that the same realities obtain in India and other parts of the world as in the west, so a certain

ironic detachment and playful tone, seen by serious practitioners as disrespectful, characterizes the writings of scholars of this kind.

I do find an unfortunate tendency among some scholars to conflate any affirmation of or identification with Hinduism with the Hindutva movement. All too

often, the accusation that someone is an adherent of Hindutva is used to discredit a scholar or to say that one’s claims should not be taken seriously. But

this can be overstated. I have identified very publicly with Hinduism and the Ramakrishna movement, and I do not find my career to have been affected in

any adverse way. I find the majority of my colleagues to be friendly and open-minded people, who respect my affiliation even if they do not share it.

Sutra Journal:

Please recommend some books and writers who have had a major impact on your life.

Jeffery D. Long:

My reading of the Gita of course led me to many other books, such as Paramahamsa Yogananda’s Autobiography of a Yogi, Aldous Huxley’sThe Perennial Philosophy, Huston Smith’s The Religions of Man, Ananda K. Coomaraswamy and Sister Nivedita’s Myths of the Hindus and Buddhists, Swami Rama’s Living with the Himalayan Masters, and eventually, the Gospel of Sri Ramakrishna

, Swami Vivekananda’s works, and The Life Divine, by Sri Aurobindo, as well as Aurobindo’s Essays on the Gita,The Secret of the Veda, and The Upanishads. I am also very fond of Eknath Easwaran’s translations of the Gita, the Upanishads, and the Dhammapada, from the Buddhist Pali scriptures. All of these authors have had a major impact on my life. I

should also mention Carl Sagan’s Cosmos, Stephen Hawking’s Brief History of Time, and some wonderful sci-fi, fantasy, and horror authors

to whose writings I repeatedly return for inspiration: J.R.R. Tolkien, Frank Herbert, Arthur C. Clarke, Isaac Asimov, H.P. Lovecraft, Stephen King, and

most recently, George R.R. Martin.

by Vikram Zutshi

November, 2015

show Vikram Zutshi's Bio

About Vikram Zutshi

Vikram Zutshi is a writer-producer-director based in Los Angeles. After several years in indie film and network TV production, then a stint as Creative

Executive at 20th Century Fox and later as VP, International Sales/Acquisitions at Rogue Entertainment, he went solo and produced two feature films before

transitioning into Directing. His debut feature was filmed at various points along the two thousand mile US-Mexico border and has since been globally

broadcast.

He is a passionate Yogi and writes frequently on Buddhism, Shaivism, Sacred Art, Culture and Cinema. As a photojournalist, Vikram often travels on

expeditions to SE Asia and Latin America and is involved with a number of charities that empower and educate street children in India, Brazil, Mexico,

Vietnam and Indonesia.

He is currently prepping Urban Sutra - a TV series about the transformative effects of Yoga in strife-torn communities and Darshana: The Aesthetic Experience in Indian Art, a feature documentary on Hindu, Jain and Buddhist Art.

www.urbansutrafilm.com

show Dr. Jeffery D. Long's Bio

About Dr. Jeffery D. Long

Dr. Long is Professor of Religion and Asian Studies at Elizabethtown College, in Pennsylvania, USA. He is associated with the Vedanta Society, DĀNAM (the Dharma Academy of North America). A major theme of his work is religious pluralism.

Dr. Long has authored three books, A Vision for Hinduism: Beyond Hindu Nationalism, Jainism: An Introduction, and The Historical Dictionary of Hinduism. He has published and presented a number of articles and papers in various forums including the Association for Asian Studies, the Society for Asian and Comparative Philosophy, and the American Academy of Religion.

show other content from Vikram Zutshi

Other Content by Vikram Zutshi

If you value this knowledge please consider donating towards its production and dissemination worldwide in Sutra Journal. Be part of the effort to bring this knowledge to the world. Donations go towards the operating costs and promotion of the Journal.

If you value this knowledge please consider donating towards its production and dissemination worldwide in Sutra Journal. Be part of the effort to bring this knowledge to the world. Donations go towards the operating costs and promotion of the Journal.