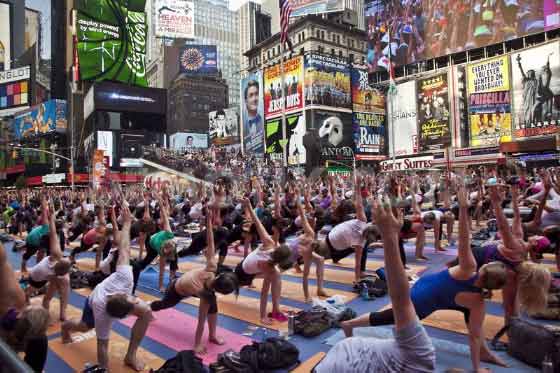

In the sixth circle. (Reuters/Mike Segar)

Vikram Zutshi:

Describe the premise of your book, Selling Yoga. What do you want the reader to take away?

Andrea Jain:

First, yoga has always been polythetic in the many pathways of its historical development and has remained so through modern postural yoga’s evolution and

recent popularization. Yoga has been perpetually context-sensitive, so there is no “authentic” or “original” tradition, only contextualized ideas and

practices organized around the term yoga. Yoga is in part what yoga practitioners say it is.

Second, contemporary consumer culture’s emphasis on self-development through rigorous body maintenance has influenced pop-culture yoga’s devotion to

fitness and health. Pop-culture yoga is a transnational product of yoga’s encounter with global processes, particularly the rise and dominance of market

capitalism, industrialization, globalization, and the consequent diffusion of consumer culture. In short, pop-culture yoga systems are products of consumer

culture and contain within them many commodities.

Third, just because pop-culture yoga is a product of consumer culture, that does not mean we can reduce it to the mere commodities of market capitalism.

When yoga insiders claim they experience yoga as transformative, extraordinarily powerful, or “spiritual,” we should take those claims seriously and

evaluate yoga (even in its popularized varieties) as a body of religious practice. In short, those who have bemoaned the consumerist branding,

commodification, and popularization of yoga as the loss of a purer, authentic religious practice are wrong. For many practitioners, yoga’s religious

qualities have not been eliminated.

Vikram Zutshi:

Describe your early experiences with yoga. How did your practice evolve over the years (if at all)?

Andrea Jain:

I suppose this will come as a surprise, but, with the exception of a yoga class I took in college and some practice here and there during field research, I

have not adopted a yoga practice. I just have not felt at home on a yoga mat. I think this has been beneficial to my scholarship though, as I think my

outsider status has served to illuminate certain points about the popular yoga tradition that insiders might not have noticed or been as willing to

highlight, such as the consumerist branding processes that characterize the yoga industry or the absence of historical ties between pop-culture yoga and

ancient yoga traditions.

Vikram Zutshi:

What made you take up religious studies as a vocation? What is your area of specialty within the field?

Andrea Jain:

My research focuses on religion in the contemporary world, with a focus on religion’s intersections with consumer culture and on yoga’s global

popularization. Like pop-culture yoga, I am a product of cultural heterogeneity and the consequent encounters between previously isolated cultural

formations in the late twentieth century. I am the daughter of a white mother who grew up in a small blue-collar Protestant community in Illinois and an

Indian father from Mumbai who was raised in an elite Jain Digambara family. Needless to say, religious and cultural heterogeneity have been lived realities

for me for as long as I remember. I first became interested in the ways religious formations were contingent on particular social contexts when, living in

Dallas, Texas, I was admitted to an elite, conservative, Christian evangelical grade school and was driven to rigorous study of the Bible for the sake of

debating my teachers on the social contingencies of the Biblical books. Of course, I couldn’t articulate it that way back then, but I knew that I was

opposed to what my teachers thought were the “right” and literal interpretations of selective parts of the Bible for what I viewed as the dangerous and

oppressive consequences of those interpretations, especially for gender, sexual, and religious minorities. When I first stepped onto campus my first day of

freshman year at college, I knew I could never leave academia as I had never felt so at home. I committed myself to a lifetime of critical reflection on

religion, but did not discover the field of religious studies until about halfway through my undergraduate career. It was in graduate school as I worked

toward a doctoral degree in religious studies that, during a research trip to India, I was first struck by the ways yoga served as an illuminating case

study of the social contingencies of religious formations, especially given the radical differences between its many premodern, modern, and recently

popularized forms. That is the short version of the story of how I became a scholar of religion in contemporary culture. As yet, I have not turned back.

International Yoga Day Times Square

Vikram Zutshi:

Yoga is popular in many countries across the world, yet nowhere is it a multi-billion dollar industry cranking out 'teachers' in the thousands (mostly

white and middle class), like in the US. Why are Americans crazy about postural yoga and why does everyone want to be a 'yoga teacher'?

Andrea Jain:

The popularization of yoga cannot be reduced to the “Westernization” and certainly not the “Americanization” of yoga. Instead, it is a result of yoga

proponents establishing continuity with contemporary consumer culture, which is transnational. Yet, there is something about the United States that makes

it a particularly booming hotspot for the contemporary yoga market.

In the United States alone, spending doubled from $2.95 billion to $5.7 billion from 2004 to 2008 and climbed to $10.3 billion between 2008 and 2012.

I suggest that, even when there are slumps in overall consumer spending, the transnational consumer cultural virtue of perfecting the body through choosing

rigorous physical fitness methods suitable to individual needs combined with the United States virtue of spending and metaphysical religion’s “shaping

role” in U.S. history has meant that the United States has become a yoga market hotspot.

Catherine Albanese (2007) places modern yoga along the same historical trajectory of what she terms “metaphysical religion” in Britain and the United

States, showing that metaphysical religion has been as vigorous, persuasive, and influential as the evangelical tradition that is more often the focus of

religious scholars’ attention. Metaphysical religion is at least as important as evangelicalism in shaping American religious history and in identifying

what makes it distinctive.

Albanese has shown that metaphysical religion has undergone vigorous growth in the nineteenth century and into and through the twentieth century and

continues in the twenty-first century.

So there is a historical and cultural precedent beyond the global dominance of contemporary consumer culture that has facilitated the extreme yoga market

growth in the United States.

I suggest there is also a socioeconomic reason for the growth.

Historical and economic research suggests that our willingness to spend is driven most prominently by our reaction to major events in our collective

memory, including wars and depressions. So how is it that even in the midst of the recent economic crisis spending on yoga skyrocketed in the United

States?

Many economists suggest people save according to universally rational calculations, saving the most in their middle years as they plan for retirement, and

saving the least in welfare states. Yet, in a recent comparative study of United States, East Asian, and European economic cultures, historian Sheldon

Garon (2012) shows that Europeans save at high rates despite generous welfare programs and aging populations. People in the U.S. save little, despite

weaker social safety nets and a younger population.

Garon concluded that people in the U.S. save too little, spend too much, and borrow excessively. Whereas other states aggressively encourage citizens to

save by means of special savings institutions and savings campaigns (the encouragement of thrift was not a relic of indigenous traditions but a modern

movement to confront rising consumption.), the U.S. government promotes mass consumption and reliance on credit (businesses and government normalized

practices of living beyond one's means).

Garon says that our willingness to spend, generally, depends in part on national character, which differs across countries and through time. More than any

other country, Garon argues, the United States elevates consumer spending to a virtue, sometimes minimizing saving. For some in the U.S., it is even

patriotic to spend, rather than to save.

So explaining the role of the United States as a yoga market hotspot, I suggest, requires us to appeal to “national character” or what Albanese calls

“American ethnicity.” While the U.S. is especially steeped in a religiosity that might not have as strong an historical precedent in other regions of the

world, a metaphysical religion that champions the enhancement of the body and facilitation of its healing, they also valorize consumer spending, elevating

it even to the status of virtue. So people in the U.S. will spend their money, and they will likely spend it, in part at least, on programs of

self-development such as yoga that are believed to bring about salvation through improving and healing the body.

Robert Bejil Productions

Vikram Zutshi:

Mark Singleton's book Yoga Body seems to have influenced many western yoga practitioners. Yet other scholars have spoken out and rubbished

Singleton's hypothesis.

Recent findings have shown not only Krishnamacharya's asana sequences but even Surya Namaskaras to be graphically described in 11th century Nepalese

Tantric texts. Do you personally feel that yoga should be separated from its cultural context and reduced to a series of mechanical movements?

Andrea Jain:

I suggest any argument concerning yoga’s “original” or “authentic” cultural context are off base. As I have already suggested in the main “takeaways” of Selling Yoga: Yoga has always been polythetic in the many pathways of its historical development and has remained so through modern postural

yoga’s evolution and recent popularization. It is important that we study the many forms premodern yoga and modern yoga take and the ways they reflect

their given cultural and social contexts. Even though there are undoubtedly certain practices and ideas that appear in more than one or even several yoga

traditions, a full understanding of those traditions necessitates that we analyze the aims or functions of specific ideas and practices within their

contexts. Highlighting aims and functions illuminates, in my opinion, far more contestations and differences than similarities. Yoga has been perpetually

context-sensitive, so there is no “authentic” or “original” tradition, only contextualized ideas and practices organized around the term yoga.

And any serious analysis of pop-culture yoga shows that it cannot accurately be reduced to “a series of mechanical movements.” As I suggested in the

“takeaways” above: just because pop-culture yoga is a product of consumer culture, that does not mean we can reduce it to the mere commodities of market

capitalism either. When yoga insiders claim they experience yoga as transformative, extraordinarily powerful, or “spiritual,” we should take those claims

seriously and evaluate yoga (even in its popularized varieties) as a body of religious practice.

In the study of yoga or any other subject, no scholar should be taken as the "final authority." We should always seek to refine, improve, and correct our

theories. The history of modern yoga is no exception. So, while I take Singleton's work to be the most convincing and authoritative scholarship on the

creation of modern postural practice to date, that is not to say that certain aspects of his work will be corrected or developed with new discoveries and

research into the topic. Either way, critical scholarship on the history of premodern and modern yoga all testify to the polymorphous history of yoga.

Vikram Zutshi:

The HAF (Hindu American Foundation) website says: "though yoga is a means of spiritual attainment for any and all seekers, irrespective of faith or no

faith, its underlying principles are those of Hindu thought. For Hindus in America, who are often faced with “caste, cow, and karma” stereotypes in public

school textbooks and mass media, the acknowledgement of yoga as a tremendous contribution of ancient Hindus to the word is important. This acknowledgement

is not to imply ownership of yoga. No one owns yoga. Rather, it is an appreciation of the richness and universality of Hindu teachings".

Which part of this statement seems wrong to you? Please elaborate.

Andrea Jain:

Today, the position that yoga has its origins in Hinduism largely results from a desire to oppose absurd stereotypes. Although such stereotypes are

unquestionably problematic, the HAF offers just one more inaccurate, homogenizing vision of yoga and Hinduism based on revisionist historical accounts.

Representatives of the HAF argue that authentic yoga is raja yoga as found in Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras with its eight limbs, of which posture is

only one. They equate postural yoga with hatha yoga, which they denounce for focusing exclusively on body-centered practices and ignoring moral and

spiritual dimensions. The HAF’s campaign prescribes yoga not only for health, but also, and more importantly, as a Hindu practice. Thus it approves of yoga

as a means to health, “But the Foundation argues that the full potential of the physiological, intellectual and spiritual benefits of asana would

be increased manifold if practiced as a component of the holistic practice of Yoga.” In other words, all practitioners should practice all eight limbs as

prescribed by Patanjali according to the HAF’s selective reading of the Yoga Sutras. Yet, as noted in Selling Yoga and many other recent

historical studies, for at least two thousand years in South Asia, people from various ideological and practical religious cultures invented and reinvented

yoga in their own images. Furthermore, the interreligious and intercultural exchanges—primarily among Hindu, Buddhist, and Jain traditions—throughout the

history of yoga in South Asia problematize the identification of yoga as Hindu.

The history of postural yoga also problematizes the definition of yoga as Hindu. As discussed in Selling Yoga, that history is a paragon of a

cross-cultural process of constructing something new in response to transnational ideas and movements.

Advocates of the HAF’s position have resisted my approach to the study of yoga, which maintains that there is no single, essentialized yoga, because they

prefer to deny the historical contingencies of their own orthodoxies, which they believe transcend human agency. But anyone interested in approaching yoga

and Hinduism in a way that accounts for their heterogeneity and context-sensitivity as well as insider and outsider perspectives and that avoids

revisionist histories must resist the tendency to locate a “right” path or a claimed essence around which all yoga systems or all Hindu traditions do or

should revolve.

@courtesy Andrea Jain

Vkram Zutshi:

In your conversation with Michelle Goldberg on Religion Dispatches, she states, "There seems to be this vaguely occult idea that through yoga we can

generate positive energy that will then ripple out into our surroundings. I think it comes from the mystification of yoga, the way contemporary teachers

try to imbue the poses with religious magic. True, if you take care of yourself, you’re more able to take care of others, but that’s not specific to

yoga—you could say the same thing of running, or spinning".

Do you agree with Michelle's statement? Is Asana exactly the same as spinning or running?

Andrea Jain:

I think it really depends on the context. In some postural yoga contexts, yoga postures are performed simply for the utilitarian gain of improving physical

fitness, primarily defined in terms of strength and flexibility. If one closely evaluates exempla from popularized yoga, it becomes apparent that it can

have robust healing, ethical, and even religious qualities.

In the postural yoga context, for example, when Iyengar’s students repeat their teacher’s famous mantra—“The body is my temple, [postures] are my

prayers”—or read in one of his monographs—“Health is religious. Ill-health is irreligious” (Iyengar 1988: 10)—they testify to experiencing the mundane

flesh, bones, and physical movements and even yoga accessories as sacred.

In the Prison Yoga Project, salvation is conceptualized as a form of bodily healing. In 2002, James Fox, postural yoga teacher and founder and director of

the Prison Yoga Project, began teaching yoga to prisoners at the San Quentin State Prison, a California prison for men. Yoga, according to the Prison Yoga

Project, provides prisoners with a path toward healing and recovery.

Yoga, even the popularized varieties, can be a profound, and sometimes religious, source of healing for some of its practitioners. But that is not the case

for all contemporary contexts in which pop-culture yoga is performed.

Vikram Zutshi:

The effects of meditation, pranayama and postural yoga on various mental and physical disorders have been widely studied at places like Harvard, Stanford

and MIT, and the results are impressive, to say the least. The Sages of old clearly knew a lot more about the mind-body complex than we do. Have you delved

into esoteric Indian concepts like Chakras, Nadis and Koshas or healing modalities like Ayurveda and TCM (traditional Chinese medicine)?

Andrea Jain:

My research does not address the underlying truth behind the metaphysical or esoteric concepts that have been a part of yoga traditions for hundreds of

years. I am, however, interested in how we define healing and its relationship to religion and conceptions of salvation. Though some might suggest that

“fitness,” “stress-relief,” and “health” are the “final objectives” of popularized varieties of postural yoga and serve utilitarian or hedonistic

self-interest as opposed to salvation or other truly religious aims, a full understanding of yoga’s religious force requires reflection on the human

tendency to seek resolutions to the problems of weakness and suffering. Wouter J. Hanegraaff (1998) suggests religion is historically concerned with the

problems of human weakness and suffering and that personal health is just one shape salvation takes in the New Age movement, and, I would suggest,

pop-culture yoga. Empirical studies have shown that yoga is effective for facilitating many forms of physical and mental healing, and what I suggest is

that this radical form of healing in the contemporary yoga world can function as a form of religious salvation.

Vikram Zutshi:

Is Yoga a catch-all phrase which can describe anything the subject wishes it to? A drunken orgy on the beach, a headstand on a surfboard or a rave party

set to thumping electronic beats? What, if anything, is constant and unchanging in the word 'yoga'?

Andrea Jain:

Although today the popular imagination relies on such distinguishing and reified categories as Hindu and yoga to think about what are

perceived as identifiable, bounded traditions, those terms have been far more fluid, contested, and unstable in their applications throughout history. And

anyone interested in approaching postural yoga in a way that accounts for its rich variation and context sensitivity as well as insider and outsider

perspectives and that avoids revisionist histories must resist the tendency to locate a claimed center or essence around which all postural yoga practice

revolves. The evidence discussed in Selling Yoga suggests that attempts to locate the essence of yoga consistently fail to do so in a way that is

consistent with both the historical record and with all or even most insiders’ experiences.

A number of qualities at different times and places have functioned as the “center” of yoga, although that center has been at the “periphery” for yogis at

other times and places. I suggest, therefore, that a polythetic approach is the most effective for understanding it. To apply such conceptual constructs

as yoga, modern yoga, or postural yoga to data accumulating around the term yoga is not to imply that each is monolithic or

static. Rather, they are living, dynamic traditions. I won’t attempt to locate what is constant in the term yoga except to suggest that there is

a almost-universal myth across yoga systems, one that grounds many practices in a shared lineage going back to ancient South Asian origins. In Selling Yoga, I do attempt to define postural yoga using a polythetic approach. I suggest, postural yoga refers to a collection of

complex data made up of a congeries of figures, institutions, ideas, and practical paths involving mental or physical techniques—most commonly meditative,

breathing, or postural exercises. It is believed to resolve the problem of suffering and to improve health, both defined in modern terms. Postural yoga

often betrays a desire to repair what is perceived as an imbalance of “body–mind–soul.” Finally, it is tied to mythologies about the historical

transmission of yogic knowledge, accumulating around a transnational community that has engaged in and transmitted what participants call yoga

—and sometimes refuse to call yoga!—since the twentieth century.