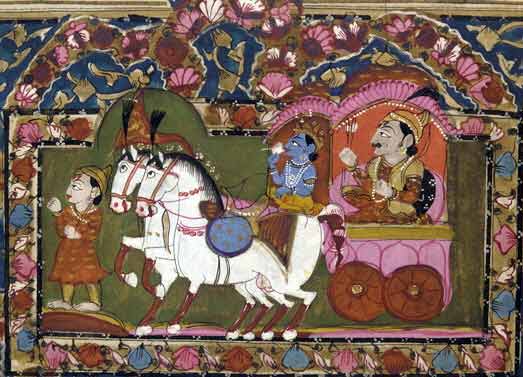

Brooklyn Museum - Vishvarupa The Cosmic Form of Krishna

Editor’s Note:

First published in Darshan Magazine.

The relationship between God and human beings has been expressed in various theologies of revelation. Some emphasize the otherness of God, while others

seek knowledge through the indwelling spirit. In the Jewish tradition, a transcendent God reveals directives to a sequence of especially chosen patriarchs

and prophets such as Abraham, Moses, Isaiah, and Samuel. They then convey the word of God to others, and provide instruction on how life is to be lived.

According to one strain of Jewish thought, God stopped communicating directly with humans after the time of the return from Babylon, approximately 500 B.C.

However, the mystical strands of Judaism, particularly schools that emphasize the Kabbalah, consider God to be an abiding presence, intimate to one’s

truest being, who can be contacted through dance and devotion.

Revelation in Christianity finds its root in the person of Jesus. The four Gospels record his life and teachings. Later theologies further articulate his

relationship with God, and speak of God’s continued presence in the world. For some Christians, the phenomenon of revelation ended with the story of Jesus

as told in the New Testament. For others, direct access to God is provided through the Holy Spirit, said in the Book of Acts to descend upon those devoted

and hopeful.

Later Christian thinkers came to regard God as tripartite: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. The father of Jesus, the traditional God of the Jewish people,

took human form in the person of Jesus, His son. After the death of Jesus, the spirit of God remains accessible through prayer and ecstasy that leads to

revelations by the Holy Spirit regarding God’s will.

Like Christianity, Islam also looks to a sacred book, the Koran, for the basis of its worship. However, in Islam, God never takes the form of a person.

Mohammed, like the prophets of Judaism, is an especially chosen messenger of God, who bequeaths to humans what Islam considers to be the final revelation.

Laws for human action are mandated in the Koran and interpreted by later scholars; for many Muslims, obedience to these laws constitutes the basis for

religious life and indicates fidelity to God’s revelation. Emphasizing interior spiritual life, Sufis—Muslim mystics—seek direct contact with God by way of

asceticism and devotional dance, affirming and celebrating the immediacy of revelation and God’s presence.

The prophetic monotheisms—Judaism, Christianity, and Islam—proceed from a common assumption: that the world was created by God, that there is only one God,

and that He has sent messages through many prophets in a variety of ways. In cultures and civilizations that do not share this essential presupposition,

revelation nonetheless is found. Among the shamanic peoples of the world, mana or spirit force, often referred to as manitou in the

native tribes of North America, takes many forms. In some societies, all males entering adulthood undergo initiations designed to foster direct

experience of this force through an extended period of fasting and solitude, culminating in a revelatory experience.

In East Asia, revelation is often associated with divination. The Yin and Yang, the creative forces of the universe, are consulted through the I Ching, in order to gain insight into how one should act in a specific situation. The medicinal and martial arts of the Far East also hinge on

the subtle balancing of these forces, externally represented in heaven and earth and internally present within the flow of energy through one’s own body.

In Confucianism, the balance of these forces is sought in one’s family life and social affairs. In Taoism, one seeks to balance Yin and Yang internally, in

search of ongoing revelation, peace of mind, and longevity.

Krishna and Arjuna on the chariot, Mahabharata, 18th-19th century, India.

In South Asia, revelation has also taken many forms. The early amulets and etchings of the Indus Valley cities indicate a concern with interiority and

purity. The Rig Veda reveals an intimate relationship between the Aryan peoples and a host of deities, from the sun (Sūrya), to the war god

(Indra), to the power of the household flame (Agni). Inspiration, an attribute of Savitar, plays an important role in Vedic life; observant orthodox Hindus

invoke Savitar each morning in the recitation of the Gāyatrī mantra. Many rituals dating from the Vedic period that are used to invoke the various deities

require elaborate preparations and the hiring of special priests for their execution. By the time of the Upanishads (c. 600 B.C.), this path to revelation

comes under scrutiny, and reflective meditation gains importance. The world celebrated in the Vedic ritual process becomes interiorized: the Brihadāraṇyaka Upanishad asserts that the vision of totality sought through the sacrifice can be obtained by focusing on the process of one’s own

body; the human body itself is said to hold the key to understanding both society and the physical world. Revelation is to be found within: the totality of

the universal consciousness (Brahman) is not different from one’s true Self (Ātman).

In the context of this specific revelatory insight, the great epic the Mahābhārata provides a model that combines both

visions of revelation—the transcendent and the immanent. In the Bhagavad Gītā section, Krishna as an avatar of God reveals to

Arjuna a major aspect of divine reality. Arjuna receives that insight and then incorporates it into his subsequent actions. The presence of God is revealed

in a specifically human context.

In the eleventh chapter of the Bhagavad Gītā, Krishna reveals to Arjuna his divine, imperishable form. This vision comprises one of the

grandest accounts of religious experience in world literature. Groping for a suitable metaphor, Robert Oppenheimer quoted this passage from the Bhagavad Gītā when he witnessed the explosion of the first atom bomb: “If the light of a thousand suns were to blaze all at once in the

sky, it would be like the splendor of that great being” (XI:12). Arjuna marvels at the many aspects of this revelatory experience, describing the many

mouths and eyes of Krishna, his celestial garlands and robes. He sees all the gods in the body of Krishna, and Krishna filling all the space between heaven

and earth, absorbing hosts of gods, seers, and perfected ones (Siddhas).

Then the splendor and glory of this sublime, paradisiacal vision turns into a vision of the “terror-inspiring,” destructive aspect of the Lord’s might.

Arjuna trembles with fear in the presence of Krishna’s form, which issues forth blazing fires of destruction. He sees all the warriors of the Kurukshetra

battlefield being sucked into the mouth of Krishna, mangled and crushed. Arjuna cries out, “As moths fly swiftly into a burning fire and perish there, so

also do these men swiftly enter your mouths to their own destruction” (XI:29). Krishna proclaims that he is none other than time itself, engaged endlessly

in the process of destroying the world. He points out to Arjuna that all persons meet ultimately with death: “Even without your action, all these warriors

standing arrayed in opposing armies shall not survive….They have already been slain by me” (XI:33-4). Krishna urges the reluctant Arjuna to perform his

duty. After more words of awe and praise, Arjuna begs for Krishna to return to his human form, following which their human dialogue resumes.

This brief summary does little justice to the account of revelation given in the Bhagavad Gītā. The beauty of this vision evokes awe and

fascination on the part of the reader, and much could be explored regarding the particulars of what was seen: the importance of Krishna’s weapons, the

specific gods included, the symbolism of the thousand heads of Krishna, his great size spanning heaven and earth. In theological terms, Arjuna was granted

a direct vision of “functional monism”: seeing God in all things and seeing all things as God. The Upanishadic precept states, “Thou Art That”; Arjuna saw

both the Thou and the That as inseparable and interpenetrating, with no beginning, no middle, and no end. God comprises and absorbs all.

The aspect of the revelation, however, that critically alters Arjuna’s decision-making process is to be found not in the grandeur and glory of the

celestial adoration of Lord Krishna’s divine radiance but rather in the terror of the Lord’s destructive aspect—Krishna’s graphic reminder of the eventual

and undeniable end to life as we know it in all its particularity. Krishna grants Arjuna a vision of death, and this compelling disclosure puts all other

things in perspective. No longer can Arjuna cling to any temporary aspect of his loved ones. The power of his enemies and of his friends disintegrates when

swallowed by the inevitability of time.

Vishnu as the Cosmic Man (Vishvarupa) Opaque

watercolour on paper Jaipur, Rajasthan c. 1800-50

Victoria and Albert Museum. The original

photograph on Flickr was taken by Val_McG

This is the crux of the revelation: the impermanence of all things and all beings is undeniable and unavoidable. When life is seen through this

perspective, one cannot do other than withdraw from attachment to that to which one had previously ascribed abiding presence. As an ongoing meditation,

this can be applied in virtually any situation in which an opportunity for or a vestige of clinging is found. This thinking frees one from being stuck in

the ignorant view that what we own is truly ours and that things are irrevocably what they appear to be. Revelatory insight comes with the perception

that, to quote the Sāṃkhya Kārikā, “I am not this, this is not mine.” By shifting one’s perspective from an “I”—dominated mode to this way of

clarity and nonpossession, one attains a lightened state of mind that allows one to move freely, doing what needs to be done but without attachment and

compulsion, in full knowledge of each situation’s evanescence.

Reflection on death stands as a hallmark of religious thought. The Bible reminds us that from ashes we come and to ashes we will return, an aspect of the

Christian faith that Roman Catholics commemorate on Ash Wednesday. Perhaps no other contemplation of death matches that of the Bhagavad G ītā in verve and drama. Krishna grants the vision of universal and inevitable death to Arjuna, who not only receives this revelation but then uses

it to dispel his fears regarding the war soon to begin. A revelation requires this sort of receptivity; if no one hears God’s word, if it has fallen on

deaf ears, then it bears no fruit. Furthermore, an insight such as that gained by Arjuna serves as a model and reminder for others. Just as Arjuna overcame his hesitancy, so also can the message conveyed inspire others to act without concern for the fruits of action. Each person must perform actions

within the world every waking moment. If one forgets, as it is so easy to do, that the world of appearance is subject to inevitable change, decline, and

retreat, then it is easy to operate within a world view that is self-centered, materialistic, and petty. In such a state one sees other people only for

what can be gained from them.

Death stands out as the great leveler, the persistent reminder that all things of this world will pass. By seeing his relatives and his teachers as if they

already had been killed, devoured in the cosmic mouth of Krishna, Arjuna gains priceless wisdom. This message does not boom forth commandments or

directives but invites us to reconsider priorities, to see the world in a new light. Revelation of this sort requires an inwardness and sensitivity. It

demands interpretative effort: in the remaining seven chapters of the Bhagavad Gītā, Arjuna struggles with how best to understand and

then apply his newfound insight. Revelation in virtually all contexts requires cultivation and application. It is not enough that Arjuna knows the eventual

outcome of the battle and, in fact, the outcome of all human existence. He must then go forth as a player in the drama, doing his duty to the best of his

ability, giving body to the wisdom gleaned while in Krishna’s exalted presence.

Such it is with all revelation and moments of great inspiration. The thrill of breaking through mental barriers is accompanied by the need to act upon the

insight gained. It was not enough for Abraham to hear God’s command to sacrifice his son; the ritual had to be prepared. It was not enough for Moses to

merely receive the Ten Commandments; they had to be obeyed by his people. lt was not enough for Jesus to preach a new path; others had to follow it.

Likewise, Mohammed’s messages from God demanded the construction of a new social order. As the Bhagavad Gītā so unforgettably

demonstrates, revelation is always a call for action to transform both ourselves and the world in which we live.